RENEWING BUDDHISM IN INDIA

Doctor Ambedkar and SangharakshitaRNBEWING BUDDHISM IN INDIA

Doctor Ambedkar and SangharakshitaA Visual Exhibition

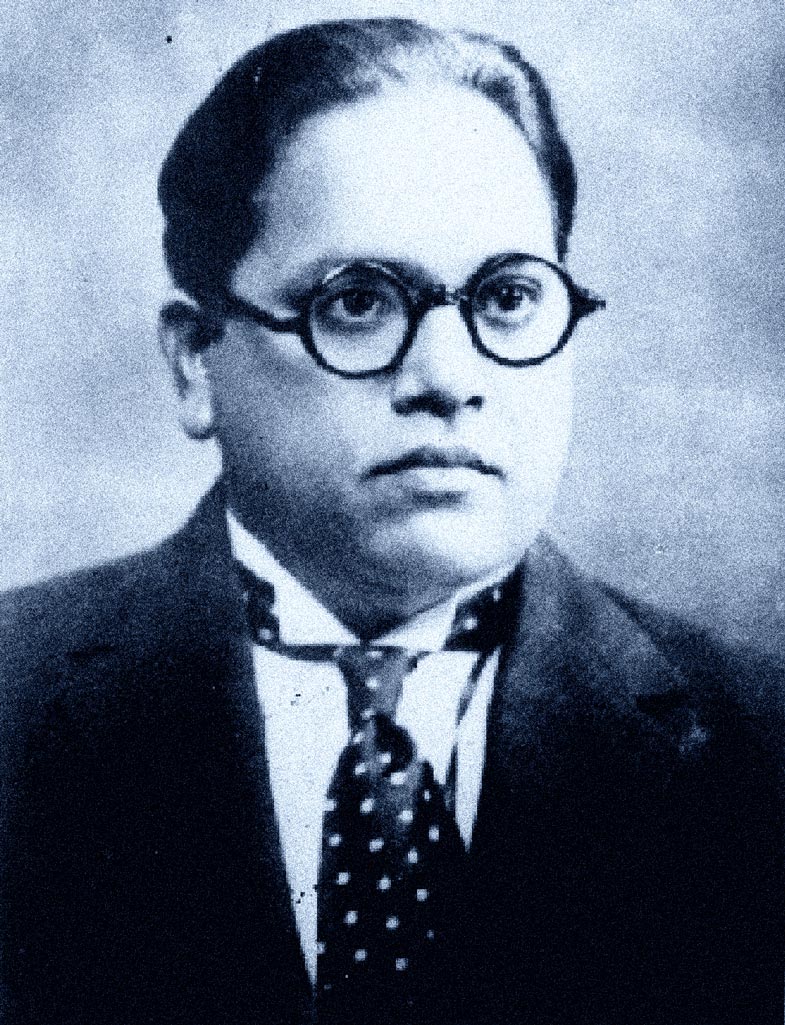

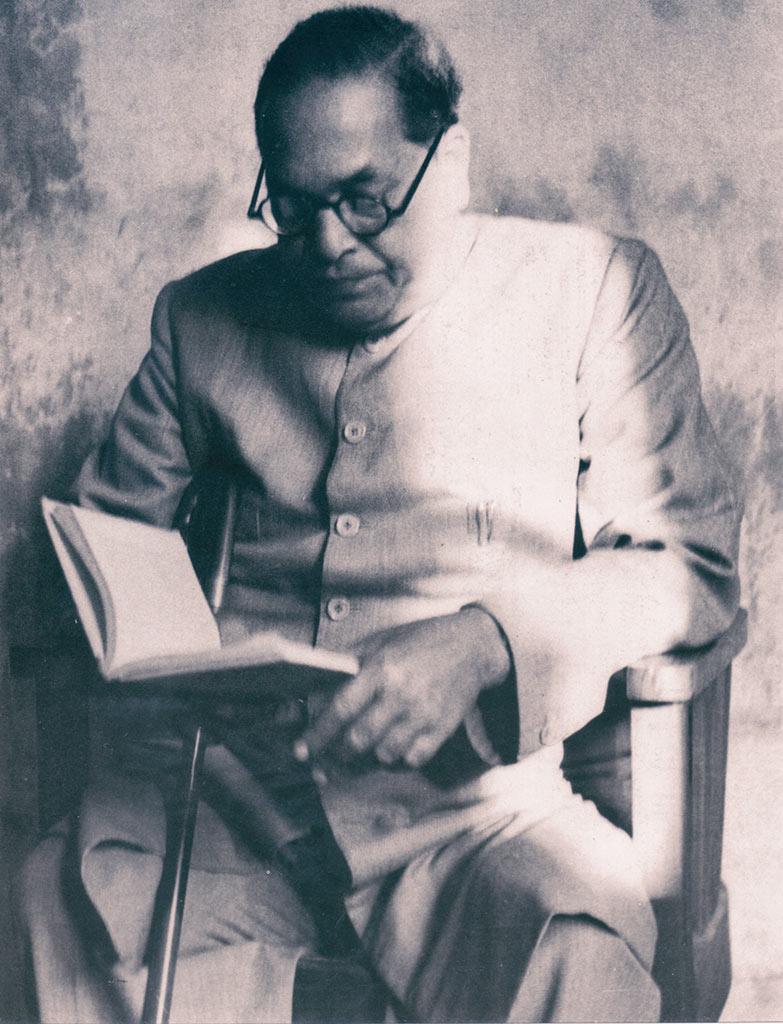

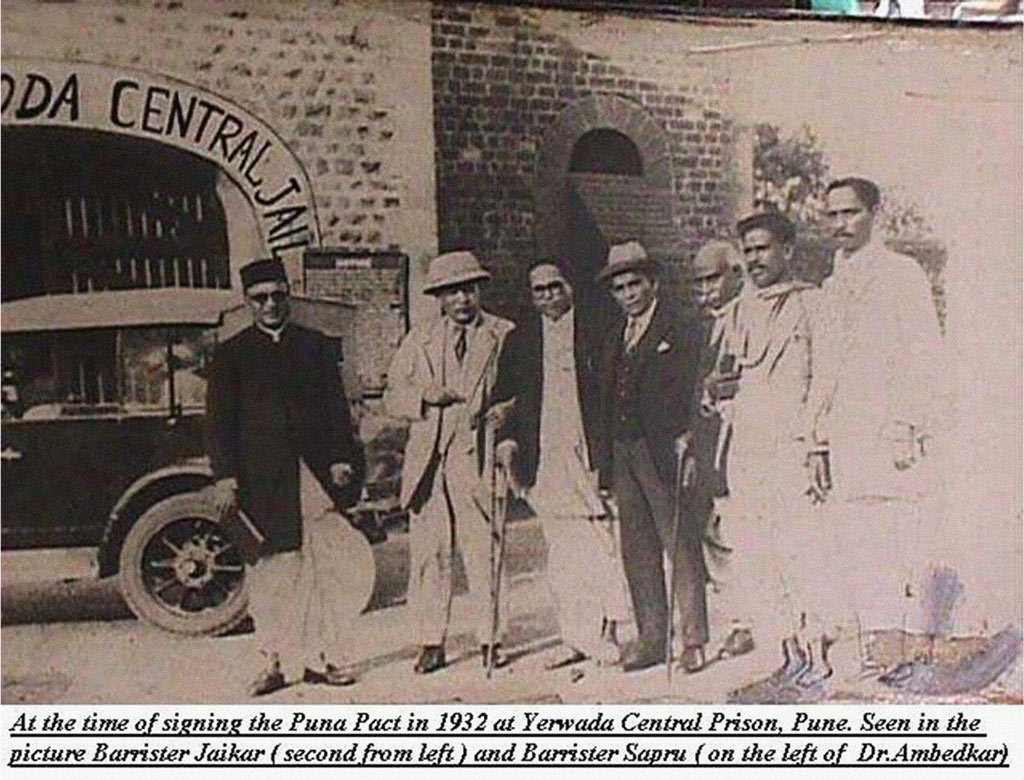

Celebrating the life and work of Doctor B. R. Ambedkar & the role of Urgyen Sangharakshita among the new Buddhists of India01. Bhimrao Ambedkar: A Brief Biography

02. Political Life

03. Social Justice

04. Water: A Symbol of the Dalit Struggle

For Dalits (formerly Untouchables), access to clean drinking water has always been a source of daily suffering and a potent symbol of their oppression.

In 1927 Ambedkar led the Chowdar Tank campaign to gain access to drinking water from a Tank, an artificial lake, in Mahad municipality. Despite having a legal right to draw water from it, the untouchables were prevented by the caste Hindus from going near the tank and in March 1927 10,000 untouchable representatives attended a conference in Mahad. Led by Dr Ambedkar they walked in procession through the town to the Chowdar tank. There he took water from the tank and drank it – followed by the other untouchables. For caste Hindus this polluted the water and they attacked the untouchables and later ritually purified the tank.

Prevalence of this practice – nine decades after Dr Ambedkar lead the Chowdar Tank protest bears testimony to the fact that his work remains unfinished. Dalits are still illegally prevented from using public wells all over India:

A dozen-odd women of Bechar village sit a few steps away from the well with their pots. They plead with youths passing by to fetch them water, but to no avail. It is over an hour and half later when finally, an old woman takes pity and starts filling up their pots, drawing water from the well. In the village of 20,000, there are 200 dalit families here whose women are made to wait on a daily basis: they cannot touch the well from which higher caste community members draw waterShardaben Solanki says her community members remain dependent on some kind-hearted Bharwad women to help them draw water from the well. “We have water supply from tube-well, but it can’t be consumed. It is laden with saline and dirt. It makes you fall sick.”

Now the dalit community is facing a boycott by upper caste villagers because they raised the issue of not being allowed to draw drinking water from the village well: “We are not only denied supply of essential commodities, but now they do not even give us water. Earlier, they would draw the water for us, but this has stopped now. We have to go to Bechraji town to buy water,” said Chiman Vaghela.

05. Why Buddhism?

Dr Ambedkar’s analysis of the political, economic and social position of Untouchables led him to the conclusion that in order to achieve emancipation they needed to give up being Hindus and convert to another religion:

If you want to organise, consolidate and be successful in this world, change this religion. The religion that does not recognise you as a human being, or give you water to drink, or allow you to enter in temples is not worthy to be called a religion. The religion that forbids you to receive education and comes in the way of your material advancement is not worthy of the appellation ‘religion’. The religion that does not teach its followers to show humanity in dealing with its co-religionists is nothing but a display of a force. The religion that teaches its followers to suffer the touch of animals but not the touch of human beings is not a religion but a mockery. The religion that compels the ignorant to be ignorant and the poor to be poor is not a religion but a visitation!

Dr Ambedkar had studied Buddhism throughout his life and had often quoted the Buddha’s teachings in his speeches. During the 1930s he had explored the possibility of converting to other religions but by the 1950s he was clear that only Buddhism offered the possibility of the freedom that the Untouchables longed for:

A religion which discriminates between one of its followers and another is partial and the religion which treats crores of its adherents worse than dogs and criminals and inflicts upon them insufferable disabilities is no religion at all. Religion is not the appellation of such an unjust order. Religion and slavery are incompatible.

Buddha stood for social freedom, intellectual freedom, economic freedom and political freedom. He taught equality, equality not between man and man only, but between man and woman.

The fundamental principle of Buddhism is equality… There was only one man who raised his voice against separatism and Untouchability and that was Lord Buddha.

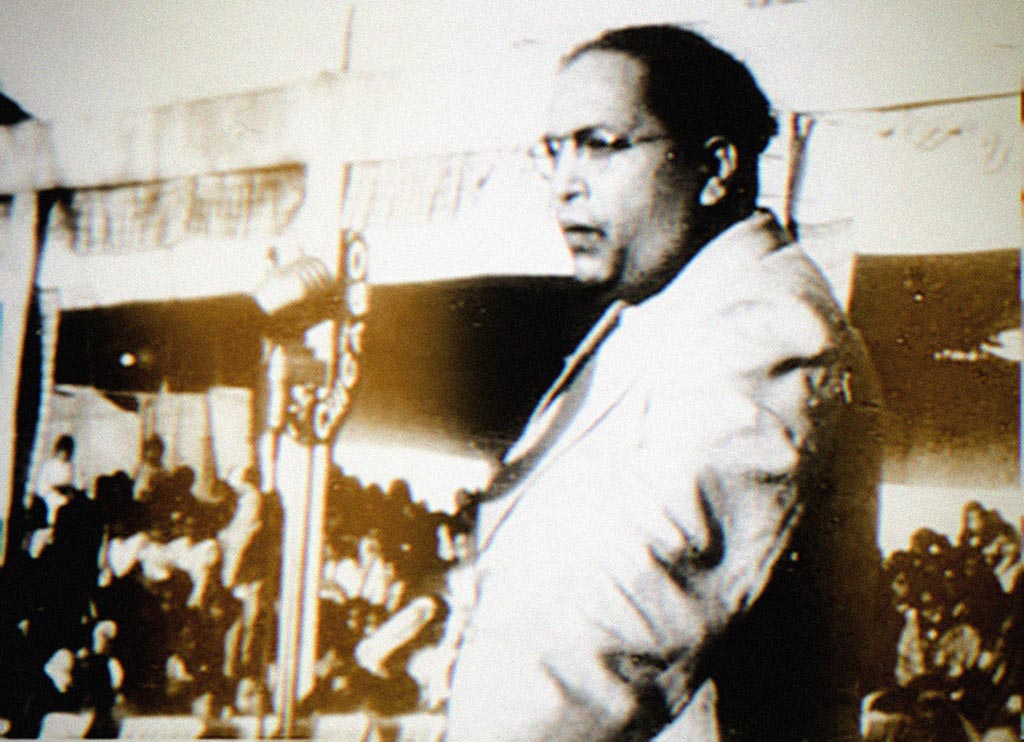

06. Conversion

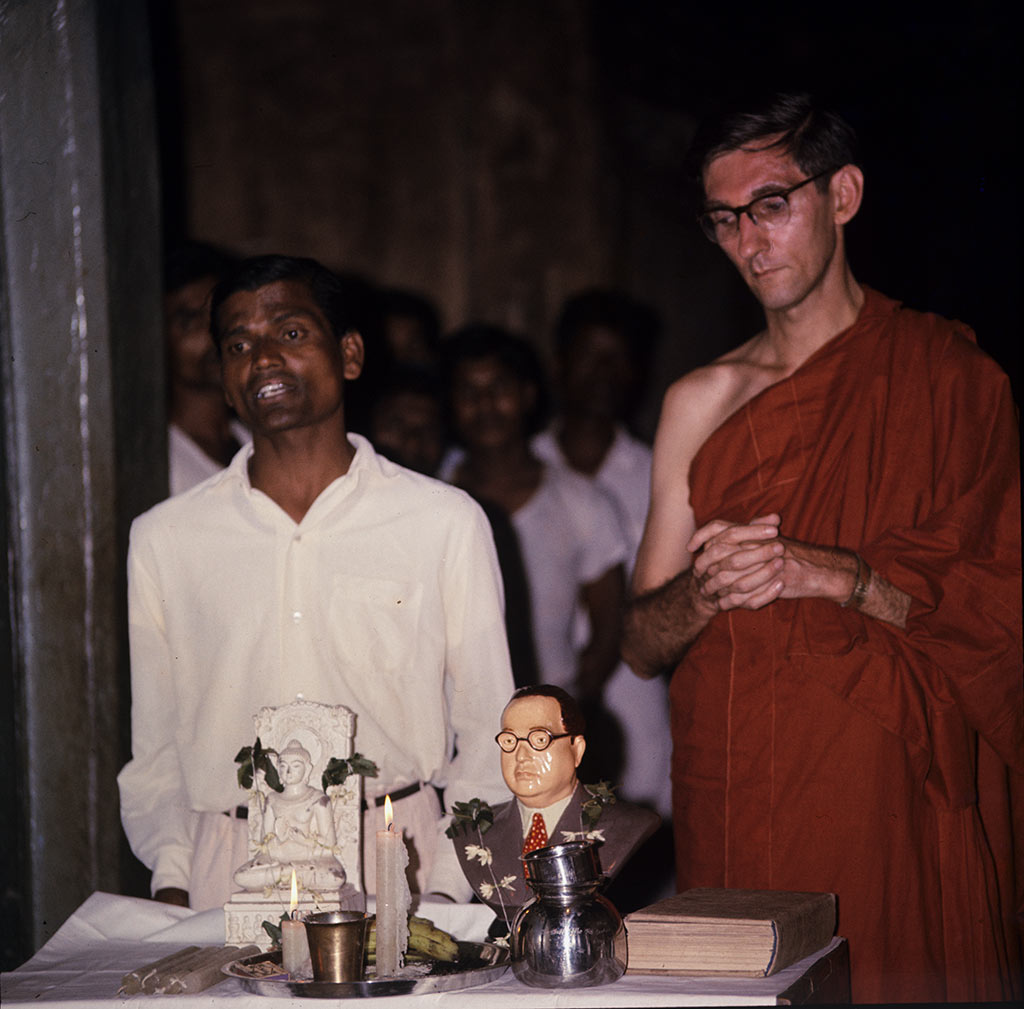

07. Sangharakshita and the New Buddhists

08. For the Benefit of All Beings

‘But though Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar had been a Buddhist for only seven weeks, during that period he had probably done more for the promotion of Buddhism than any other Indian since Ashoka. At the time of this death three quarters of a million Untouchables had become Buddhists, and in the months that followed hundreds of thousands more took the same step – despite the uncertainty and confusion that had been created by the sudden loss of their great leader… This was Ambedkar’s last and greatest achievement, so that even though it was as the Architect of the Constitution of Free India and the Modern Manu that he passed into official history and is today most widely remembered, his real significance consists in the fact that it was he who established a revived Indian Buddhism on a firm foundation. It is therefore as the Modern Ashoka that he really deserves to be known, and the statue standing outside the parliament building in Delhi should really depict him holding ‘The Buddha and His Dhamma’ under his arm and pointing – not for the benefit of the Untouchables only, but for the benefit of all mankind – in the direction of the Three Jewels’, Sangharakshita.

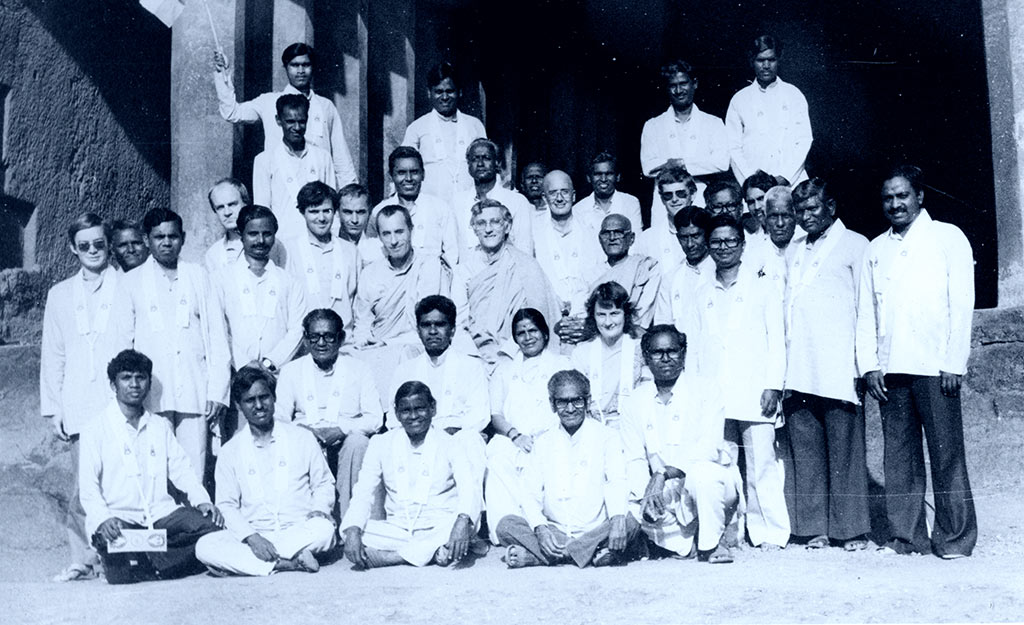

‘Wherever I went I moreover saw, as I had seen time and time again all those years ago, how overwhelmingly grateful Ambedkar’s followers were for whatever Buddhist teaching they received. This time, however, they would not have to wait for years before they heard another lecture on Buddhism. This time they were in contact with a new Buddhist movement, a movement that was the direct continuation of Ambedkar’s work for the Dharma, so that even after I had gone there would be plenty of opportunities for them to hear lectures, to learn how to meditate, and to go on retreat. There would, in short, be plenty of opportunities for them to practise Buddhism, and it was in the individual and collective practice of Buddhism that – Ambedkar believed – they would find the inspiration which would enable them, after centuries of oppression, to transform every aspect of their lives’, Sangharakshita writing about a teaching tour in the winter of 1981-82.

‘The greatest thing the Buddha has done is to tell the world that the world cannot be reformed except by the reformation of the mind of man and the mind of the world.’

Dr. Ambedkar.

What Doctor Ambedkar Means To Me?

Recordings by contemporary Indian BuddhistsShraddhavajri

Ratnashri and Vijaya

Vaibhav

Media Resources

New Dharma resources on Doctor Ambedkarweb design by dharmachakra

original exhibition & image curation by danasamudra

original exhibition design by dhammarati