Life of the Buddha

A resource for teachers, parents and students (aged 8 to 12)

INTRODUCTION

What westerners call Buddhism arose from the Buddha’s experience of Enlightenment. The title Buddha means ‘One who is awake’.

At his Enlightenment, the Buddha became awake to the truth of How Things Really Are. Buddhists believe the Buddha was not a God, a prophet or a messiah, but a human being developed to an extraordinary degree.

For Buddhists, the life of the Buddha is an inspiration. They may worship or revere the Buddha as a teacher, a hero and an exemplar; as the one who discovered the way to Enlightenment.

More introductory info (click to open)

The Buddha’s teachings were preserved through a strong oral (spoken) tradition for five hundred years before being written down in Sanskrit and Pali. The Pali Canon (more than 26 times the length of the Bible) is the only surviving complete collection of this oral tradition. The Pali Canon does not contain a complete, sequential account of the life of the Buddha, but the Buddhacarita, or ‘Acts of the Buddha’, a Sanskrit work composed about 100 years later, also provides a basis for accounts of his life.

The Buddha was born Siddhartha Gautama, a member of a wealthy aristocratic family of the Shakyan clan, in what is now Nepal, around the year 560 BCE (Before Common Era). For twenty-nine years, Siddhartha had lived a well-to-do existence, but increasingly found a life devoted to material pleasures empty and unfulfilling. He experienced a deep sense of dissatisfaction and also a desire to find meaning in life. The legend of the Four Sights represents, in dramatic form, a spiritual crisis or turning point. His response to this spiritual experience was to ‘Go forth’; to leave behind security and comfort in order to seek an answer to his questions about life. The Going Forth and the Enlightenment are key incidents in the life of the Buddha.

In the Indian subcontinent there was, and still is, a tradition of wandering holy men and teachers. It was then commonly believed that the way to find spiritual truth was through self-mortification and extreme asceticism. After six years, Siddhartha realised that extreme self-denial was not a useful spiritual practice. Instead, he advocated a middle way between the two extremes of denial and self-indulgence.

ABOUT THIS RESOURCE

7 sections, each with video components, questions and suggested activities. Click on a section to jump straight to it.

1 The Boyhood of Siddhartha

2 Going Forth

3 Enlightenment

4 The Buddha Decides to Teach

5 Teaching the Dharma

6 The Last Days of the Buddha

7 The Buddha Image

1 The Boyhood of Siddhartha

In the first chapter we look at the early life of Siddhartha Gautama, who later became the Buddha.

Discuss/consider before watching the video

Suffering

Siddhartha’s father tried to shield him from all the unpleasant things in life.

- Do you think it is possible to avoid all suffering and unhappiness in your life? Why?

- What things in life cause us to suffer or be unhappy?

- Have you ever met someone you admired and wanted to be like?

Material aimed at teachers/parents

Suffering

Siddhartha’s father tried to shield him from all the unpleasant things in life.

- Do you think that will be possible to avoid all suffering and unhappiness in your life? Why?

- What things in life cause us to suffer or be unhappy?

- Have you ever met someone you admired and wanted to be like?

Turning points

Siddhartha saw the Four Sights and felt that he could not ignore the questions they raised. Sometimes we see, or experience, events that make us stop and think: illness, bereavement and loss, for example.

- Can you remember such an event?

- What was it that made you stop and think?

- What did you do as a result?

Questions for after the video

1. What were the first three things Siddhartha saw on his visits to Kapilavastu? How did he feel, seeing them?

2. Write about three things you feel unhappy about when you look around you.

3. Buddhists are taught to remember that everybody, everywhere, experiences some pain or unhappiness in life. How do you think this might affect the way they feel about other people, including people they have never even met?

4. Asita told the king that his son would grow up to be either a great kind or a wise holy man. Which would you chooose to be: a great leader or a wise holy person? What might be the similarities and differences between two such people? Do you have to choose?

Activities

1. Imagine you are Siddhartha. Using pictures from newspapers and magazines, or drawing your own pictures, make a poster of the Four Sights as you see them today, where you live or in other parts of the world. Explain to the class, or write about, how you feel seeing these things.

2. Write and perform a short play about Chanda the charioteer coming home after seeing the Four Sights with Siddhartha. Show Chanda talking with a friend about happened, what Chanda thought about it and what he thought was on Siddhartha’s mind as they returned home.

3. The fourth person Siddhartha met had a strong effect on him. Imagine you are Siddhartha, writing your diary after you’ve met this person. Write about what the wise man looked like,

how he behaved and how you felt being with him. Or imagine you personally met a wise woman or man near where you live, and write about that. How did you know they were wise?

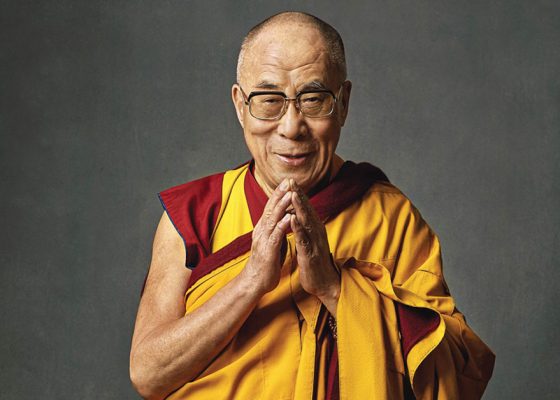

4. Webquest Many people think the Dalai Lama is a great leader and a wise holy man. He is a Buddhist monk. Using the internet or books, find out about him and make a wall display or a PowerPoint presentation. Explain who he is, what kind of person he seems to be, what he wants and what he is doing (and not doing) to achieve his goal. Not all his people agree with his approach. What do you think?

If you want others to be happy, practise compassion.

If you want to be happy, practise compassion.

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama

2 Going Forth

In the second chapter Siddhartha leaves home.

Discuss/consider before watching the video

- Have you ever had to make a big change in your life? What did you feel or think about it?

Material aimed at parents/teachers

Many people have suggested Siddhartha was selfish to leave his wife and child. It is possible that he had no wife or child and that they appear in the story as symbols for things which stop us from making progress in life; but suppose he really did have a wife and son. If he thought that finding an end to suffering for all human beings was even more important than staying with his family, could we accept that?

- Could there ever be a good reason for leaving one’s family?

The process of growing up is, to some extent, one of leaving things behind. In order to move on we sometimes have to leave things behind. Changing classes at the end of a year, or moving from junior to secondary school are examples of this.

- Have you ever had to make a big change in life?

- Why did you make the change?

- What did you have to leave behind?

Making up your own mind

When Siddhartha gave up the ascetic life and began to take food again, his five friends left him. However, he was not afraid to admit that he had made a mistake and that he must carry on alone.

- Are there any occasions when you have had to admit that you have made a mistakeCan you relate an experience when you have had to make up your own mind?

- In what situations do you experience group pressure?

- How do you deal with group pressure?

Questions for after the video

1. Siddhartha did not find it easy to leave his home and family, but he needed to move on, to find the answers to his questions about life. Our lives are full of change too.

Can you think of a time when you have had to move on? Write about what you had to leave behind, what you were looking forward to and how you felt or thought about it.

2. Siddhartha thought that doing things which were tiring and hard work for the body might help him become a wiser person. He tried some things which were so hard they were dangerous, like not eating properly. Instead of feeling wiser, he found he only became weak and ill, so he stopped.

However not all hard work is bad for us. It’s only bad for us if we overdo it. Have you ever done something which was difficult or tiring but helped you feel better? What did you feel or think about it and why?

3. When Siddhartha gave up his ascetic life and began to eat again, his five friends left him. However, he was not afraid to admit he had made a mistake and carry on without them. Think of a time when you have experienced pressure from others. How did you feel or think about it? How did you make up your own mind?

Activities

1. Imagine you are a friend of Siddhartha and you know he is secretly planning to leave home soon. Write and ask him at least two questions about why he is planning this. Now imagine you are Siddhartha, writing back. How will you explain what you are doing?

2. Imagine you are Chanda, the chariot driver. You have returned to the palace with Siddhartha’s jewels and ornaments, as instructed. Write the story of Siddhartha’s leaving home as you would tell it to the king the next morning. Explain what Siddhartha has done and why.

3. Webquest Aung San Suu Kyi is a Buddhist who has spent her life working to end the suffering of her people, in Burma. This has meant being separated from her husband and children for many years. In groups, and using the internet or books, find out about her and write a PowerPoint presentation to tell her story. What has she done for her people? How has it affected her family? Do you think it was worth it?

3 Enlightenment

In the third chapter Siddhartha reaches Enlightenment and becomes the Buddha.

Discuss/consider before watching the video

- Do you know anyone you consider wise? How can you tell? What do they understand about life? How did they come to know it?

Material aimed at parents/teachers

Impermanence

When the Buddha became Enlightened, he understood that all things are impermanent.

- What signs of impermanence and change do you see in your life and the world around you?

- Can you think of anything that is permanent and will not change?

- What effect does thinking about impermanence have on you

- How might recognising impermanence affect the way you live your life?

Wisdom and kindness

- Do you know anyone you consider wise?

- How can you tell they are wise?

- What is it they know?

- How did they become wise?

- Is it possible to be wise but not kind, or kind but not wise?

- What might be the dangers of being kind without enough thought?

Human potential

The Buddha taught that all human beings have the potential to grow and change and eventually become Enlightened.

- What things do you think can and can’t be changed

about yourself? - Do you believe that everyone can change for the better? Can you give examples from your own experience?

- Are there some people who cannot change? If so, why do you think this is?

- What do you think causes people to change?

- Do you think there is a limit to the positive changes a person can make in themselves? If so, can you say what that limit is? What prevents people going beyond it?

Action – ourselves

The scripture, the Dhammapada, says that our lives are shaped by our minds: we become what we think. (see below)

- Do you think this is true?

- In your experience, what has shaped who you are now?

- Does what you do and say affect you?

- How does what you think affect you?

- Who is responsible for how you feel?

- What are ‘positive’ actions?

- What are ‘negative’ actions?

- How can you change the way you think and feel? What things might affect the sort of person you

become in the future?

Action – the world

The Buddha’s Law of Karma states that actions have consequences.

- Do you agree?

- Can you think of anything that you do that has no consequences?

- In what way do our actions affect the environment?

- Why care for the environment?

- What can you do that will make a difference?

- In what way does the environment we create affect us?

More material aimed at parents/teachers

Defining the undefinable!

Enlightenment is beyond words. Nevertheless, people do need to know something about it in order to move towards it! Traditionally, Enlightenment is described in four ways: negatively, positively, paradoxically and symbolically.

Negatively

As cessation: an Enlightened being is free of the unhealthy mental states of greed, hatred and ignorance. These are sometimes known as the Three Poisons or Fires. Nirvana/nibbana is known as the extinguishing of these fires. (Nirvana/nibbana = blowing out.)

Positively

in terms of the characteristics of an Enlightened being, which are:

- supreme bliss

- profound wisdom (seeing into the nature of reality)

- infinite compassion, springing from a love for all life

- a radiant, unlimited consciousness

- boundless energy

Paradoxically

The Mahayana texts employ paradox to describe Enlightenment in order to emphasise that it is beyond words and concepts. For example, it is said that a Buddha abides in a state of ‘non- abiding’, or that Nirvana is attained by means of ‘non-attainment’.

Symbolically

Enlightenment is also represented through metaphor, poetic description or symbol. For example, it is described as the Cool Cave, the Island in the Flood, the Further Shore or the Holy City. There are elaborate Mahayana accounts of the Happy Land, or the Pure Land. There are also symbolic forms, including the stupa (reliquary) and symbolic images of the Buddha and other Enlightened beings.

The Law of Conditionality

The fundamental insight gained by the Buddha at his Enlightenment was that all phenomena whatsoever – from a tsunami to your every passing thought – arise in dependence upon existing conditions. When those conditions change, so do the phenomena they gave rise to. This is the teaching of pratitya samutpada (in Sanskrit; paticcasamupada in Pali). It follows from this that all phenomena are seen as interdependent and constantly liable to change.

The Law of Karma

The word karma literally means ‘action’. The Law of Karma states simply that human willed actions have consequences.

This is an important Buddhist teaching. Although it can be difficult to grasp fully, some appreciation of this law is essential to an understanding of Buddhism.

The Law of Karma springs from the Buddha’s Law of Conditionality, which states that all phenomena are subject to change, dependent on conditions. The Law of Karma is the Law of Conditionality applied to human actions.

Some Buddhist traditions teach that everything which happens to us is the result of karma. According to the earliest scriptures, however, there are other kinds of causation too. Thus not everything that happens to us is the result of Karma. The Law of Karma does not attempt to explain all cause and effect processes to which we are subject.

The Law of Karma is like a scientific law; it merely explains how things happen. It does not indicate the existence of a law-giver. Buddhists believe there is no-one who rewards or punishes us.

Because of the Law of Karma, Buddhism teaches that people can change themselves through their own actions.

Rebirth

Karma continues throughout the process of death and rebirth. According to the Law of Conditionality, all things change. However, Buddhism says there is continuity, a connecting flow, not only from moment to moment but from life to life. One traditional illustration of the death-rebirth process is of a new candle being lit from the flame of a dying candle. The ‘second’ flame is neither a new flame nor the old one, but has arisen in dependence upon the ‘first’ one.

Note that the Buddha’s teaching on rebirth differs from that of the Vedic tradition of his time, which taught that an unchanging soul or essence (the atta/atman) passes from one life to the next, like water poured from one vessel into another. This can be found today in some strands of what we now call Hinduism. Instead, the Buddha taught anatta/anatman, or ‘no [fixed or unchanging] self’.

About the stilling exercise for parents/teachers

Meditation and ‘stilling’

Buddhist meditation is a system for training the mind and developing wisdom and compassion. Most Buddhist traditions regard it as indispensible to the development of profound awareness.

Stilling exercises in the classroom or at home

While it is not appropriate to teach ‘Buddhist meditation’ to pupils in the context of an RE lesson, much benefit can be obtained from doing a simple ‘stilling’ exercise. This exercise can give pupils a sense of the the pleasure and benefits to be gained when we quieten our minds, as well as the challenges we may encounter.

The recorded 7-minute stilling exercise can be done without the need for special equipment, such as meditation cushions or stools.

Make sure you leave enough time to complete the exercise. It can be jarring to be suddenly halted by the school bell, and the benefits could be lost through a hurried conclusion to the lesson.

Pupils will get most out of the exercise if there is enough time at the end for them to discuss their experience.

Discuss after the stilling exercise

- How did you find it?

- Have you ever done anything like this before?

- Was there anything you found difficult about the exercise?

- Was there anything you found easy, or particularly enjoyed?

- How easy did you find it to concentrate on what you were trying to do?

- If you found yourself distracted, what sort of things distracted you?

- Can you remember how you felt before the exercise?

- How do you feel now?

- Had anything changed in your experience by the end of the exercise?

- What did you learn from trying to do this exercise?

- How do you think this sort of exercise might help people?

- What do you think Buddhists mean by ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ states of mind?

Questions for after the video

1. Siddhartha started off as a person just like us. However, Buddhists believe that when he became Enlightened he became perfectly wise, compassionate, peaceful and happy. He said that anyone could do this if they wanted to. He also said there was no limit to how much a person could change for the better.

Do you think that everyone can change for the better? To support your opinion give examples of people you know.

2. The Buddha said everything is impermanent. This means that everything changes and nothing lasts for ever. Just as a plant needs soil, air, water and sunshine in order to exist, everything depends on other things for its existence and changes when those conditions changes or are no longer there. The Buddha said that this was true of people and everything else in the universe.

What do you feel or think about impermanence? If you really believed that nothing lasted for ever, how do you think it would affect the way you live?

3. The Buddha also said that people don’t want things to change or come to an end. They want things to be permanent. Wanting things to stay the same is one of the things which causes unhappiness and suffering.

Do you agree with him? To support your opinion, give an example from your experience.

Activities

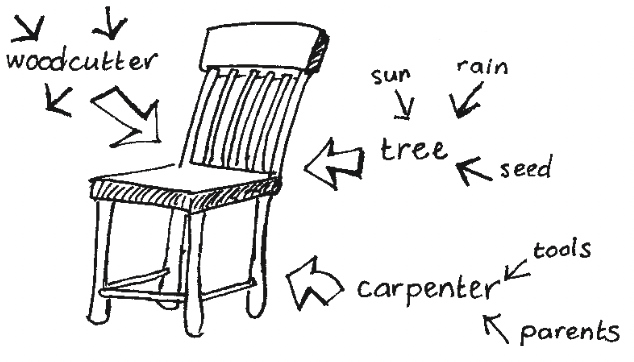

The Buddha said he had seen that all things are dependent on other things for their existence, and that all things are therefore interconnected.

1. Individually or with a partner, brainstorm things that change. Can you think of anything that is permanent?

2. Write a haiku, or short poem, to express the idea that all things change and how you feel about this.

3a. Look below at the interdependence web for a chair. How far can you extend it?

3b. Plot an interdependence web for the following: a woollen jumper, a plate of chips, a car, yourself.

3c. Choose one of your interdependence webs. Will all the links always stay the same? Say what might happen if one of the links changed.

4. Try the ‘stilling’ exercise below, to give you an idea of what it’s like to meditate

Stilling Exercise

4 The Buddha Decides to Teach

In the fourth chapter the newly Enlightened Buddha decides to teach others what he has discovered.

Discuss/consider before watching the video

- What do plants always grow towards?

Material aimed at parents/teachers

The lotus: a symbol of development

The image of lotus plants at varying stages of development symbolises the Buddha’s vision of humanity in progress towards ‘Enlightenment’, the full ‘flowering’ of human potential, attainable by all. Growing from the depths of muddy ponds, lotuses literally grow from darkness to light. As in many traditions, darkness and light are metaphors for ignorance/confusion and wisdom.

- How have you made progress since last term/ last year?

Moving towards the light

Plants grow not just towards light, but in response to light. Light is one of the conditions upon which the development of a plant depends. It is the same with people, Buddhism says: to be fully human, people need, and respond to, the ethical beauty which is inherent in wisdom and compassion.

- What things inspire you to do your best, be kinder, more helpful; or to do something to help others or make the world a better place?

- Plants grow towards light. What do you think it might mean if we said that people also move towards the light?

Flowering/ blossoming

Sometimes we talk about people ‘flowering’ or ‘blossoming’, meaning that they are becoming happier and more confident, making the most of their lives. This seems to relate to the lotus as a symbol of Enlightenment. If we think about it, we can often identify what has helped us to feel like this; for example praise, affection, being listened to and taken seriously.

Identity

The wanderer Upaka meets the newly Enlightened Buddha. Though he senses immediately that this is no ordinary person, he is at a loss to categorise him. A Buddha, an Enlightened being, is undefinably different from the unEnlightened. A Buddha is not just a very nice person! Having gone beyond the normal way in which the rest of us see the world, s/he cannot even be said to be human, except in physical form. Enlightenment is the nirvana/ nibbana (snuffing out/extinction) of greed, hatred and ignorance/delusion (the Three Fires/ Poisons). Going beyond these three things represents an unimagineable, total transformation of one’s entire being.

This story also points to the very human tendency to label people as types, rather than to see them as individuals, for who they really are. The Buddhist teaching of anatta holds that since everything is change and process, there is no such thing as a fixed self. For practical purposes we need labels (girl, boy, black, white, car etc) but, ultimately, nothing and nobody can be fixed or categorised. To label people is to fix them and limit them.

-

What kinds of labels could we use to describe the different people in this class?

-

When are those labels useful/necessary?

-

When are labels unhelpful or unkind?

-

What do we have in common, despite labels?

Questions for after the video

1. In his mind’s eye, the Buddha saw a pond full of lotuses growing towards the sunlight. Why do you think this reminded him of human beings and the way they develop?

2. What did Upaka ask the Buddha?

Activities

1. Imagine you are Upaka and you’ve just met the Buddha. After many days of meditation he has the answers to all his questions. You have asked whether he is a human being, an angel, a spirit, or something else and he just keeps saying,“No, I’m a Buddha.”

Write about how he seems to you: what he looks like, what kind of mood he is in, how he treats you, etc. Why do you want to know what kind of being he is? What do you think of his answer? This can be a poem if you like.

2. Group activity Upaka really wanted to know what type of being the Buddha was. The Buddha said he did not belong to any of the groups or types that Upaka could think of, because he had now become a Buddha; someone who is Enlightened. An Enlightened person is perfectly compassionate and wise; someone perfectly free of greed and hatred, who perfectly understands the way life is. Such a person is not like anything we can imagine.

Brainstorm all the types or groups people in your class belong to, and the labels people give themselves and other groups; eg. Punjabi, white, boys, redheads, Christians, etc. Does each person just have one label? Get people to stand in one kind of grouping, and then another. How much do people move? Does anyone not move at all? What does this tell you about people and labels?

If you want, you can do this as a Venn diagram, with circles for different groups.Where do the circles overlap?

5 Teaching the Dharma

In the fifth chapter the Buddha tells five old friends what he has discovered.

Discuss/consider before watching the video

- If someone walked into the room now and said they were now perfectly wise and kind, what would you say?

Material aimed at parents/teachers

- What’s the difference between being clever and being wise?

- What’s the difference between someone who thinks they know everything, and someone who really is profoundly wise?

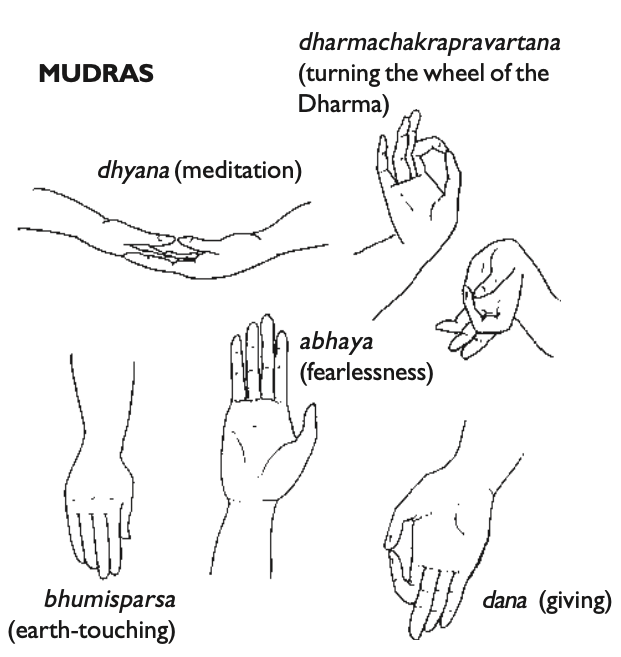

The Pali scriptures record the Buddha as teaching his five old friends the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path. This first teaching is known as the Dhammachakkappavattana/ Dharmachakrapravartana – the (first) turning of the ‘wheel of the Dharma’. The eight-spoked wheel represents the Buddha’s

teaching; in particular his Noble Eightfold Path leading to

Enlightenment.

The Four Noble Truths

The Buddha taught that suffering is caused by wanting things and experiences to make us happy; when they are bound to let

us down because everything changes and nothing lasts for ever. Here, ‘suffering’ primarily refers to the emotional suffering/unsatisfactoriness we feel about the things which happen to us.

For example, it is possible for two people to have the same fatal illness and suffer quite differently from one another because of their attitude; eg “Why me? It’s not fair! I want to live!” and “I so want to live, but how can I make sure my last few months are of greatest benefit to everyone?” They may not be able to do anything about their illness, but they can choose to cultivate a positive attitude to it.

- Can anything make you happy for ever?

The Noble Eightfold Path

Despite its name, this is not a sequential path, but a list of eight areas covering the whole of life, in which a Buddhist can make effort. The first two areas are about seeing life according to the Buddha’s understanding, and maintaining an emotionally engaged intention to follow his teachings.

Questions for after the video

1. What do you think the Buddha’s old friends thought when they saw him coming towards them?

2. What made the Buddha’s old friends decide to take him seriously

3. Why did the Buddha and his five newly Enlightened friends set off in different directions to teach people what they had discoverd?

Activities

1. Using the Pupil Information Sheets from the Enlightenment and Teaching the Dharma sections write a short play or draw and write a cartoon strip about the Buddha meeting his five old friends for the first time. What does he teach them, and what kinds of questions do they ask? What is it that they start to understand? Show how their attitudes change as they start to understand and take him more seriously.

2. From newspapers and magazines, collect examples of suffering in the world, with pictures. With a partner arrange your examples under two headings: suffering which can be changed and suffering which cannot be changed.

Explain your choices.

3. Think of a goal you want to achieve. Write down eight things

you need to do to achieve it.

4. Conditionality/ interconnectedness game The class stands in a circle. Secretly, each person chooses two other people in the group. No matter what happens, you are going to try to keep an equal distance between you and these two people. (It doesn’t matter whether the three of you are in a V shape or a straight line.)

When the teacher says “Go”, everyone starts to walk around. Things may speed up as each person has to move around more to stay equidistant from their two secret partners. Afterwards, discuss what you noticed.

Option Get someone to leave the room before you give the instructions. Invite them to come in while the class are moving about. They have to guess what the rules are and why everyone is moving.)

(Note The group will come to a standstill, because the game is a limited example of interconnectedness and conditionality. In the universe the connections between phenomena are infinitely more complex, such that nothing comes to a standstill. This game was invented by Joanna Macy, American Buddhist and Systems Theory specialist.)

The Noble Eightfold Path

- Right vision/understanding

- Right intention/emotion

- Right speech

- Right action

- Right livelihood

- Right effort

- Right mindfulness

- Right meditation/concentration

The Four Noble Truths

1. Everyone experiences unhappiness in life.

2. Our unhappiness is caused by wanting things which can’t make us happy.

3. Good news! It’s possible to stop all this wanting.

4. It just takes training. The way to do it is to follow the Noble Eightfold Path leading to freedom from unhappiness.

6 The Last Days of the Buddha

In the 6th chapter we look at the Buddha’s passing away, and the spread of Buddhism.

Discuss/consider before watching the video

- What do you think is the most important thing anyone can achieve during their lifetime?

Material aimed at parents/teachers

- How do people usually feel when someone or something they care about dies? Why is this?

Death is usually an occasion for loss and grief, for Buddhists as much as anyone else. The scriptures record that at the death of the Buddha some of his followers were grief-stricken.

Others reportedly remained serene. This does not mean they were hard-hearted or alienated; simply, they were Enlightened or near to it and had seen deeply the truth of impermanence as a normal part of life.

Tradition holds that with the death of the Buddha’s physical body he entered into ‘Parinirvana’, or final Enlightenment ‘without remainder’. This means that, having gained Enlightenment during his lifetime, with his death came freedom from endless birth and death.

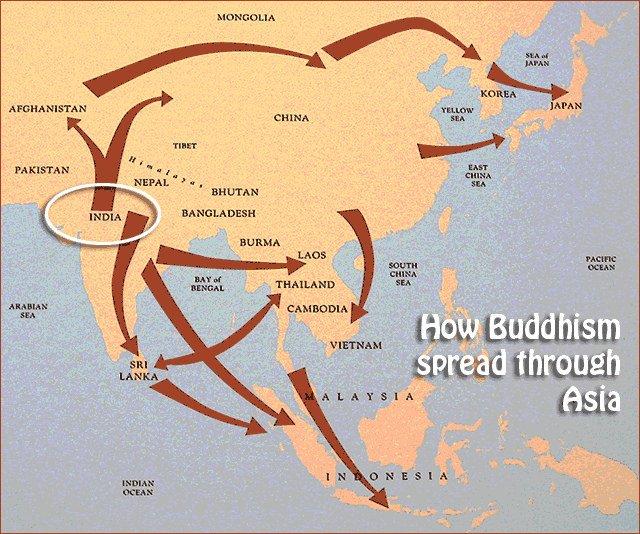

The Spread of Buddhism

Buddhism originated in northern India around the year 560 BCE. About 250 years later, during the reign of the Emperor Ashoka, (289-232 BCE) Buddhism began to spread throughout India. Ashoka also asked monks to take the Dharma to other countries: south- east to Sri Lanka, north towards Nepal and Tibet and west towards the kingdoms of the Greek Empire.

Over the centuries, the practice of Buddhism gradually spread, until at one time a third of the population of the world was Buddhist. As it took root in different countries, Buddhism adapted to different cultures without sacrificing its basic principles. This resulted in the development of many different forms of Buddhism. Many of these schools have now spread to the west.

Theravada Buddhism

In the countries to the south and south-east of India people practise a form of Buddhism known as the Theravada, or “Way of the Elders”. Its yellow, orange or brown-robed monks study and teach the Dharma. They regard the monastic life as very important and believe that living as a monk or nun is the best way to become Enlightened. Traditionally, boys follow the monastic life for a time as part of their upbringing. The lay people follow the Buddha’s teaching and help the monks by giving them money, food and robes.

Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana literally means the ‘great way’. People in the countries to the north and north-east of India, including China and Tibet, follow this form of Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism emphasises the importance of compassion. There are many different ‘schools’ of Mahayana Buddhism.

Buddhism spread to China at the beginning of the Christian era and to Japan about 500 years later. The Pure Land schools are based on devotion to the Buddha Amitabha. The Zen school lays stress on meditation as the way to gain Enlightenment.

Vajrayana Buddhism

Vajrayana means the ‘diamond way’. This form of Buddhism spread from India to Tibet around 700 CE. Ritual and worship play a particularly important role. Many Tibetans chant mantras – sacred phrases – as they go about their daily lives. Tibetan monks and nuns wear maroon and yellow robes. The Dalai Lama is a Vajrayana teacher. The Buddhists of the Russian republic of Kalmykia, are Vajrayana and follow him.

Buddhism in the west

From the 1950s onwards, Buddhism became increasingly well known in the west, and most of the major Buddhist traditions are now being practised by westerners. There are also new Buddhist movements founded by westerners, experimenting with new ways of practising the Buddha’s teachings.

Questions for after the video

1. Ananda was very upset that the Buddha was dying. He picked out one particular about the Buddha that he would remember. Fill in the gap in this sentence from the video: “My teacher, who is so ——-, is about to leave us.”

2. What three good things would you like people to say about you when your life is over?

3. The scriptures say that the Buddha’s last words to his friends were “All things are impermanent. With mindfuless, strive on.” What do you think he meant?

Activities

1. Rewrite the story of the Buddha’s last days as if you were his good friend Ananda.

2. Some of the Buddha’s friends remained perfectly calm when he died, but it was not because they did not care. Draw or paint a picture of the Buddha dying, surrounded by his weeping friends, and his perfectly calm friends. How will you show the difference?

3. Make a list of the key events in the life of the Buddha. Re-tell the story of his life in the form of a comic strip, with words and pictures.

4. Arrange these four events in the life of the Buddha in order of their importance to the future of Buddhism:

– birth of Siddhartha

– his going forth

– his Enlightenment

– teaching the Dharma

Explain your choices. Now choose a different order and do the same thing again. Is any event unimportant?

7 The Buddha Image

In this final chapter we find out about Buddha figures.

Discuss/consider before watching the video

- why do you think people keep pictures of people they love or admire?

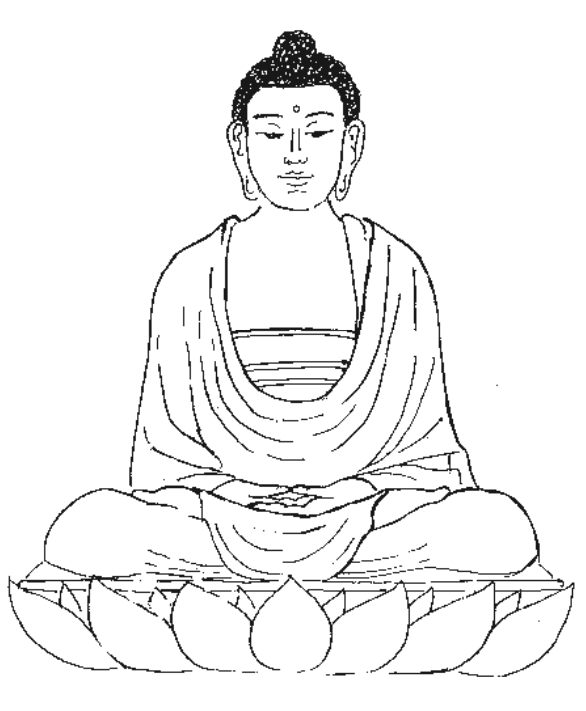

Material aimed at parents/teachers

Reminders

The Buddha image reminds Buddhists of the Buddha and all he represents for them. When we love and admire someone a great deal we sometimes keep pictures or mementoes to remind us of them.

- Do you have any pictures, posters or reminders of people you like or admire?

- What do you like or admire about these people?

- How does the picture or memento help keep them in mind?

Body language

The Buddha image communicates particular qualities to Buddhists. We communicate our- selves to others through the way we dress, sit and move.

- How do you dress to express personality?

- Does what you wear affect how you feel?

- Does what you wear affect how other people respond to you

- Can you tell what a person is like from looking at them?

- We communicate through ‘body language’ all the time. Does how we move and hold our body affect how we feel about ourselves? Does it affect the way others respond to us?

Perfection

Buddhists believe that the Buddha perfected himself.

- What qualities would you most like to develop?

- What qualities would a perfect person have?

- Is it possible to be perfect?

- If not, what stops us?

- If you think it is possible, how can it be achieved?

During the Buddha’s lifetime, his followers would venerate him by making offerings and coming to sit silently in his presence. After his death, the Buddha’s remains were divided and housed in funerary mounds called stupas. Early Buddhists visited stupas to worship. Making offerings, and chanting verses of praise, they renewed their undertaking to strive for Enlightenment. The holy sites connected with the Buddha became places of pilgrimage.

The earliest existing Buddha-figures come from Gandhara, today in Afghanistan. The image, while being a reminder of the historical Buddha, was primarily a symbol of Enlightenment. Gandharan artists copied local images of the Greek god Apollo, an athlete with long hair tied up in a topknot. Gradually in India a code developed showing the ‘marks of a superior being’; for example, the long ear lobes and the ushnisha, or point on the top of the head. As time passed other symbolic features developed, such as mudras, posture and colour, based on the visionary experience of Buddhist meditators.

Some figures from the Mahayana and Vajrayana schools of Buddhism represent Enlightened archetypes, rather than the historical Buddha. They can be in male or female form, look peaceful or wrathful, have coloured skin and wear the clothes and ornaments of royalty. All seek to convey particular qualities of the Enlightened mind and have symbolic and ritual significance to the devotees of particular traditions of practice.

Questions for after the video

1. The Buddha is usually shown with a point on his head, a dot between his eyes and long ears. What do these things symbolise?

2. Buddha figures vary a lot. Why do you think this is?

Activities

1. Look at a Buddha image and draw it from observation.

2. Think of someone you admire and want to be like. Draw a picture of them. Make up symbols to show their special qualities. Explain the symbols.

3. Using the internet, look at figures or images of the Buddha (sometimes called Shakyamuni Buddha). Choose three or four different figures or images and write a presentation explaining where they come from, what they have in common and what’s different; such as the hand positions.

Glossary of Buddhist terms

Most Buddhist terms were originally expressed in Pali and Sanskrit, languages of ancient India. Where they differ, first the Sanskrit then the Pali version (in brackets) are given here. Buddhists also use words in their own languages, or the languages of other traditionally Buddhist countries in Asia.

Bodhgaya The holy site associated with the Buddha’s Enlightenment

Bodhi ‘Awakening’ or Enlightenment

Buddha ‘One who is awake to the Truth’; who is Enlightened

Dharma (Dhamma) ‘The Truth’; also the teaching of the Buddha

Gautama Family name of the Buddha

Karma (Kamma) ‘Action’ – the Law of Karma states that actions have consequences.

Kushinara The Buddha’s place of death or parinirvana; known today as Kushinagar

Mahayana The ‘Great Way’: one of the three major forms of Buddhism

Mudra A ritual gesture or hand movement, especially as found in Buddha images

Nirvana (Nibbana) ‘Extinguishing of the fires’ of greed, hatred and ignorance. The state of Enlightenment

Pali The ancient Indian language in which the scriptures of the Theravadin Canon were preserved

Parinirvana (Parinibbana) The final passing away of the Buddha

Sangha Variously used to mean: 1. the community of Buddhists; 2. monastics; 3. all those who have gained Enlightenment since the Buddha

Sarnath The place where the Buddha first taught the Dharma

Siddhartha (Siddhattha) The given name of the Buddha as a young man

Theravada The ‘Way of the Elders’: main school of Buddhism in south-east Asia

Vajrayana Literally means ‘diamond way’ and describes one of the three major forms of Buddhism

Vinaya Rules of monastic life followed by monks and nuns