DELVING DEEPER - ages 15-16

Beliefs and Values

Conditionality or Dependent Origination

The Principle of Conditionality, The Law of Causation and Conditioned Co-production are all translations of the Pali term paticcasamupada.

The Principle of Conditionality, The Law of Causation and Conditioned Co-production are all translations of the Pali term paticcasamupada.

Buddhists believe that as part of his Enlightenment experience, the Buddha understood the nature of existence. He put his realisation, which is essentially beyond words, into the conceptual form of paticcasamupada, or The Principle of Conditionality.

This principle teaches that

- everything comes into being and is maintained by a complex web of conditions

- everything is part of the network of conditions maintaining something else

- nothing exists completely independent of anything else

- everything ceases when the conditions that maintain it cease

- the whole of existence is a ceaseless process of flux and change

- conditionality applies on all levels of existence from the physical environment to the human mind

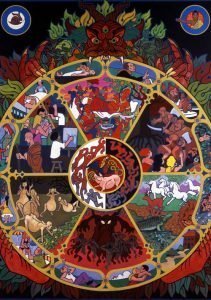

Check out this interactive wheel of life and this BBC resource.

If this is, that comes to be;

from the arising of this, that arises;

if this is not, that does not come to be;

from the stopping of this, that is stopped.

The Four Noble Truths

Part of the Enlightenment experience of the Buddha was the direct ‘Knowledge and Vision of Things as they Really Are’; he realised the Truth, or the Dharma.

Part of the Enlightenment experience of the Buddha was the direct ‘Knowledge and Vision of Things as they Really Are’; he realised the Truth, or the Dharma.

He decided that it was possible to help others to realise the Truth for themselves and gain Enlightenment and began to formulate the Dharma, the teaching that leads to Enlightenment. So he put his realisation, which is essentially beyond words, into the conceptual form of the Law of Conditionality.

The Four Noble Truths are an application of the Law of Conditionality to the problem of human suffering. This teaching follows an ancient Indian medical formula:- illness, cause, cure, remedy.

The Noble Eightfold Path is the fourth Noble Truth – the remedy for human suffering.

The Four Noble Truths Buddhism begins by addressing suffering because no-one can deny the existence of pain. Simply put, the Four Noble Truths are:

1. Dukkha – PAIN – physical suffering, psychological pain and existential dissatisfaction.

2. Samudaya – The ORIGIN of Pain, which is craving.

3. Nirodha – The CESSATION of Pain, which is achieved by overcoming craving. The Third Noble Truth asserts that man can achieve Enlightenment through his own efforts.

4. Magga – The WAY to the Cessation of Pain, which is the following of the Noble Eightfold Path.

The Four Noble Truths are a fundamental Buddhist teaching. Despite their concise and simple format, they are a profound teaching that can be understood on deeper and deeper levels.

So, does that mean that cancer is the result of craving? It might be. Lung cancer could be caused by craving for cigarettes, for example. It is also dependent on a number of other conditions: nuclear fallout, genetic predisposition, etc.

However we must distinguish between physical suffering and psychological suffering.

Buddhists who believe in the teaching of rebirth might say (without any sense of blame) that a person’s cancer was partly the result of their being born in a physical body, yet again, as a result of their endless craving for physical existence, when they could have chosen to practise the Dharma more, leading to a rebirth in a different, non-physical state.

Other Buddhists might just say that cancer is one of the many difficult things we may have to face in life, which are hard to explain. What matters is how we respond to it.

One person with cancer may be eaten up with bitterness: “Why me? It’s not fair” etc. This is the kind of suffering which comes with aversion – craving for things to be other than the way they are. This person now has two kinds of suffering. Another person with cancer could choose to see their illness as an opportunity for changing lifestyle, making the most of the time they have left, making sure their friendships are in good repair etc. Because they don’t resist the reality of their situation by craving for things to be different, they suffer less emotional and psychological pain.

Of course, many people with any kind of suffering will experience a mixture of these two attitudes.

See also these resources from the BBC on the Four Noble Truths.

Noble Eightfold Path

- Right vision, or understanding: understanding that life always involves change and suffering; realising that following the Noble Eightfold Path is the way to overcome suffering and be really happy.

- Right emotion: commiting oneself to wholeheartedly following the path.

- Right speech: speaking in a positive and helpful way; speaking the truth.

- Right action: living an ethical life acording to the precepts.

- Right livelihood: doing work that doesn’t harm others and is helpful to them.

- Right effort: thinking in a kindly and positive way.

- Right mindfulness: being fully aware of oneself, other people, and the world around you.

- Right meditation, or concentration: training the mind to be calm and positive in order to develop Wisdom.

The Dharmachakra is a Buddhist symbol for the Dharma. It usually has eight spokes to represent the teaching of the Noble Eightfold Path.

Although the ‘Path’ has eight separate steps, they are not intended to be followed one after another. The Buddhist way of life involves all of them and enables Buddhists to train themselves in every aspect of their lives.

All Buddhists should strive to follow the Noble Eightfold Path, whether they live in a remote monastery in Tibet or in a flat in the middle of a city. How do Buddhists follow the Eightfold Path?

Here are some quotes from Buddhists who are trying to follow this ancient Buddhist teaching in a modern setting.

RIGHT VISION

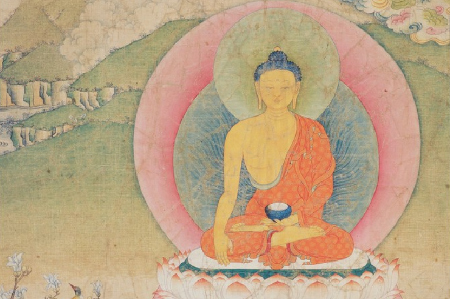

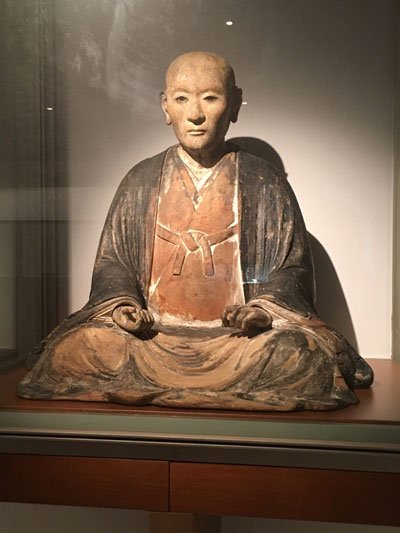

Before I can practise Buddhism at all, I have to have some idea that there’s something to work towards. When I look at the Buddha image I remember that I, too, can be like that. I can become happier, wiser and more compassionate. I too want to gain Enlightenment. That’s my goal, my vision.

RIGHT EMOTION

It’s no good wanting Enlightenment in my head, if, in my heart, I can’t be bothered. One way I can motivate myself is by meditating. I can also inspire myself by reading some Dharma books.

RIGHT SPEECH

We have a strong effect on others through our speech and communication. I need to speak kindly and truthfully. If I tell the truth, especially when it isn’t easy, I can develop honesty and fearlessness. By being truthful I do myself honour….What a challenge it is to be really honest and always kind.

RIGHT ACTION

We’re engaged in actions all day. Buddhism says that the key to Right Action is intention. Behind every action is a state of mind. If I catch myself in a negative state of mind, I can choose to act differently and so practise Right Action.

RIGHT LIVELIHOOD

We try to avoid any kind of work that might increase suffering in the world. We don’t want to harm the environment, animals or humans. So we avoid work involving weapons, tobacco or alcohol. Instead, I want to find work that can help the world. I like to work with other Buddhists because it keeps me on my toes. It’s not easy to forget the Noble Eightfold path when your mates are practising it too.

RIGHT EFFORT

I can find myself in different states of mind from one moment to the next. What can I do about this? My states of mind can affect what I do. So I need to ask myself through the day: ‘What state am I in?’ Then I can change that by making more effort – I can change how I think and feel .With Right Effort I can develop a more positive and brighter outlook.

RIGHT MINDFULNESS

Often we are not aware of how we are feeling or what we are doing. If we can become more aware we can live in the present moment and transform our lives. Staying aware is a practice that can lead to happier states of mind. Instead of rushing through a job, I can slow down and even enjoy what I am doing. Right mindfulness makes the most of the present moment.

RIGHT MEDITATION

I begin my day with meditation. Why do I meditate? I can only transform myself in all the other steps of the path, if I know myself well. Meditation helps me to develop calm and peaceful states of mind. Then I can begin to see myself more clearly. With the help of meditation, I can gradually progress through ever higher states of mind along the path. I can get nearer and nearer to Enlightenment, even if takes much effort and many lifetimes.

The Threefold Way

The Threefold Way is another way of describing the Buddhist path. Its stages are:

The Threefold Way is another way of describing the Buddhist path. Its stages are:

- ethics

- meditation

- wisdom

Many people in the West come to Buddhism first through meditation classes. Traditionally, however, ethical behaviour is regarded as the start of the Buddhist journey towards the perfect wisdom of Enlightenment. Anyone can learn meditation, but without the clear conscience which comes with knowing that they have acted ‘skilfully’ (kusala), they will not progress all that far.

Ethical action in Buddhism is described by the Precepts, and motivated by kindness and awareness of karma – that our actions will have consequences.

The Threefold Way is circular rather than linear: as we act more and more ethically, including making the effort to meditate regularly, we will increase in our understanding of the Dharma, the Way Things Are. This makes it easier to act ethically and meditate, and thus our wisdom grows yet further.

Can you arrange the stages of the Noble Eightfold Path under the headings of the Threefold Way?

The Middle Way

The Middle Way is the path between extremes.

The Middle Way is the path between extremes.

We can see how it emerges from the Buddha’s own experience: having grown up in luxury and found that unsatisfying, he tried asceticism: the life of a wandering holy man, fasting and subjecting his body to various physical experiences intended to subdue craving and bring about wisdom. Finding this did not lead to an understanding of the truth, he came to advocate a simple and dignified life, providing just what was necessary to support a life devoted to spiritual practice.

At a more sophisticated level, the Middle Way represents the path between extreme views. Reality is ultimately indefinable, nothing can be pinned down to This or That. Most importantly, it applies to the question of nihilism and eternalism.

Buddhism says everything in life is dependent on other things, which keep changing. (See Conditionality/Dependent origination and the Three Marks.) This means that nothing is completely independent. Nothing has any fixed self. Nothing is permanent.

It would be tempting to say that nothing really exists at all. This is nihilism.

The opposite of this would be to say that everything, though mostly changeable, has something about it which lasts forever – a soul or essence. This is eternalism.

What the Buddha saw at his Enlightenment was that Reality was neither of these. The Way Things Really Are is somewhere in between. You can’t say that what we call ‘a tree’ exists or does not exist. It isn’t really a thing. It’s a process; it appears more or less the same for periods of time, but it is constantly changing.

Karma

The Law of Karma states that actions have consequences.The word karma simply means action.

The Law of Karma states that actions have consequences.The word karma simply means action.

The Law of Karma

- is an important Buddhist teaching; some appreciation of this law is essential to an understanding of Buddhism.

- springs from the Buddha’s teaching of the Principle of Conditionality. The Buddha understood that everything which exists is subject to change, dependent on conditions.

- is the application of the Principle of Conditionality to the process of life and death.

- is like a scientific law; it merely explains how things happen. It does not indicate the existence of a law-giver. There is no one who rewards or punishes us.

- does not mean that everything that happens to us is the result of Karma. In a complex web of conditions, there can be many reasons why something happens.

- applies only to deliberate, or ‘willed’, actions.

- asserts that skilful actions, based on compassionate, generous and clear states of mind, will have positive consequences and

- unskilful actions, driven by negative states of greed, hatred and ignorance, will have negative consequences.

Greed, hatred and ignorance are know as the Three Root Poisons. They can be seen represented by the cock, snake and pig at the hub of the Wheel of Life.

All actions of body, speech and mind have an effect. Change will happen anyway, but because of the Law of Karma, it is possible to change for the better.

Our life is shaped by our mind,

we become what we think.

Suffering follows an evil thought

like the wheels of a cart follow

the oxen that draw it.

Our life is shaped by our mind;

we become what we think.

Joy follows a pure thought

like a shadow that never leaves.

For another presentation of karma, see Access to Insight website.

Nirvana

Enlightenment is beyond words.Nevertheless, people do need to know something about it in order to move towards it!Traditionally, Enlightenment is described in four ways; negatively, positively, paradoxically and symbolically.

Enlightenment is beyond words.Nevertheless, people do need to know something about it in order to move towards it!Traditionally, Enlightenment is described in four ways; negatively, positively, paradoxically and symbolically.

Negatively, as Cessation.An Enlightened being is free of the unhealthy mental states of greed, hatred and ignorance. These are sometimes known as the three poisons or the three fires. Nirvana is known as the extinguishing of these fires.(Nirvana = blowing out)

Positively, in terms of the characteristicsof an Enlightened being, which are:-

- supreme bliss

- profound wisdom (seeing into the nature of reality)

- infinite compassion (springing from a love for all life)

- a radiant, unlimited consciousness

- boundless energy

Paradoxically

The Mahayana texts (from the second great phase in Buddhist thought) employ paradox to describe Enlightenment in order to emphasise that it is beyond words and concepts.e.g. a Buddha abides in a state of non-abiding…or

Nirvana is attained by means of non-attainment…

Symbolically

Enlightenment is also represented through metaphor, poetic description, or symbol.e.g.

- the Cool Cave

- the Island in the Flood

- the Further Shore

- the Holy City

- there are elaborate Mahayana accounts of the happy land or the Pure Land

- the stupa, and symbolic images of the Buddha and other Enlightened beings

The Three Marks

The Buddha taught that all existence has three fundamental characteristics or marks. These are known as the Three Lakshanas.

The Buddha taught that all existence has three fundamental characteristics or marks. These are known as the Three Lakshanas.

Dukkha – suffering or unsatisfactoriness

- is an inescapable aspect of life – we will all suffer old age, sickness and death

- includes emotional and psychological suffering – frequently one gets what one doesn’t want and doesn’t get what one does want!

Dukkha literally means an ill-fitting chariot wheel – like a ride in a chariotwith an ill-fitting wheel, life is often bumpy and uncomfortable.

Anicca – impermanence

- all things come into existence dependent on conditions

- nothing stands still or lasts forever

- nowhere is there anything fixed, permanent or eternal

Anatta – no self.

Because nothing is permanent there is

- no fixed unchanging essence or soul

- no unchanging creator God

- unlimited potential to change and grow

Buddhists recognise that in order to achieve wisdom they need to develop for themselves a deep understanding of these truths, through meditating and reflecting upon them.

Community and Tradition

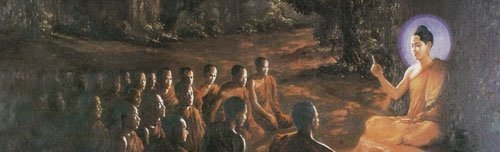

The Buddha in 60 seconds!

- The Buddha was born Siddhartha Gautama around the year 560 BCE. He was a member of a wealthy aristocratic family of the Shakyan clan in what is now Nepal.

- For twenty-nine years he lived a protected and luxurious existence but found a life devoted to material pleasures empty and unfulfilling.

- Disobeying his father’s orders he went out into the nearby city and saw The Four Sights – old age, sickness, death and a wandering holy man.

- These sights heightened his sense of dissatisfaction and his desire to find meaning in life. He decided to leave his privileged existence and Go Forth.

- He spent six years as a wandering Truth-seeker, learning from religious teachers and undertaking harsh ascetic practices as a path to the Truth.

- Following The Middle Way between the extremes of denial and self- indulgence he gained Enlightenment while meditating under a tree (afterwards known as the Bodhi Tree).

- Buddhists believe that at his Enlightenment the Buddha understood the nature of existence and discerned the cause of suffering.

- After his Enlightenment he was known as the Buddha, which means ‘One who is awake [to the Truth about the way things are]’.

Sangha

Sangha has several meanings.

Sangha has several meanings.

- It refers to the spiritual community of Buddhists worldwide and throughout time.

- In the Theravada tradition it refers generally to the monks only. (A more detailed description here.)

- Most importantly, it refers to all those who have gained Enlightenment – the aryasangha, or noble sangha. It is mainly this that is meant by the third ‘refuge’ or ‘jewel’. Buddhists ‘take refuge’ in the sangha; they are able to place their trust in the effectiveness of the Buddha’s teaching, because they see that many have done this before them and reached Enlightenment.

Buddhist Schools

1. Theravada Buddhism

The Elders

The Elders

The Theravada school of Buddhism traces its history back to the Great Council about 100 years after the time of the Buddha, when a split occurred between two schools of monks. While most monks asserted that they were following all the rules given to them by the Buddha, others, who identified themselves as the followers of the senior monks, insisted that there were further rules to be followed. Of these, the Theravada is the one school still in existence. The word theravada means the way of the elders.

Sri Lanka

Some 150 years later, Theravadin monks sailed to the island of Sri Lanka with Mahinda, son of the famous Indian emperor Ashoka. They took with them a cutting of the Bodhi Tree, under which the Buddha had gained Enlightenment at Bodhgaya, and the memorised teachings of the Buddha.

The Pali Canon

Over 100 years later, upheavals in Sri Lanka threatened the survival of the monastic sangha, and therefore of the 500 year-old oral transmission of the teaching. This threat prompted the writing down of the Buddha’s teaching. The Pali Canon, the Theravada collection of scriptures, comprises these earliest texts, written down in Sri Lanka 30 years before the beginning of the Common Era, about 500 years after the death of the Buddha.

The Pali Canon is the oldest complete collection of Buddhist scriptures and is divided into three collections: The Vinaya Pitaka or collection of monastic rules, The Sutta Pitaka or collection of the Buddha’s discourses, and the Abhidhamma Pitaka, the collection of ‘further teachings’. The Theravada school reveres its sacred texts as an accurate record of the original and true teaching of the Buddha.

The Arhat

Theravada Buddhism emphasises the quest to become a perfectly Enlightened One, or arhat. An arhat is one who has eradicated the poisons of greed, hatred and ignorance. The path to arhatship consists of the practice of ethics, meditation and wisdom. The Theravada tradition holds that it is through living as a monk or nun that one is most likely to achieve that goal.

The Buddhapadipa Temple (Theravada) in London was the first Buddhist temple in the United Kingdom.

2. The Bodhisattva Path

The Mahayana and Vajrayana schools of Buddhism emphasise that

The Mahayana and Vajrayana schools of Buddhism emphasise that

- the principle of Enlightenment pervades the whole of existence

- all beings have within them the potential to become Enlightened

- the highest goal is to seek Enlightenment not for oneself alone, but for the sake of all beings; this is known as the Bodhisattva Ideal

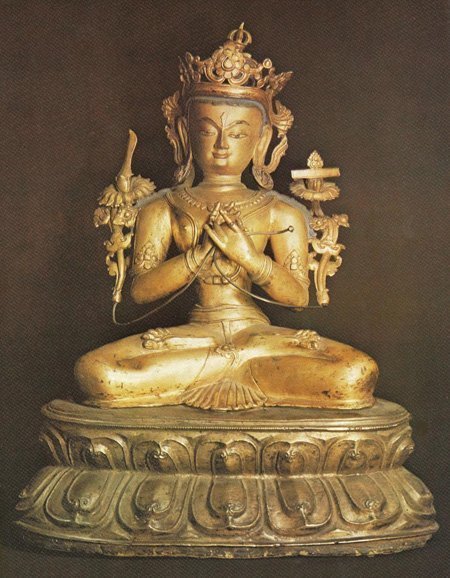

The word Bodhisattva literally means Enlightenment Being. A Bodhisattva vows to free all beings from suffering and to help them gain Enlightenment for themselves.

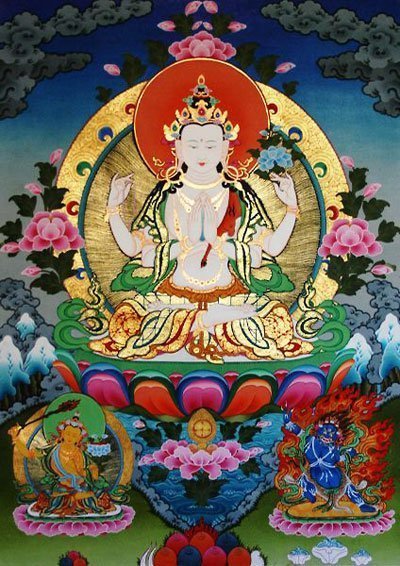

Avalokiteshvara – the Bodhisattva of Compassion

- represents supreme compassion

- views the suffering of the world with the wisdom and compassion of Enlightenment

- is very popular in Mahayana Buddhist countries

- is known as Chenrezig in Tibet, Kuan Yin in China and Kannon in Japan

- in one of his many manifestations, Avalokiteshvara has 11 heads and 1,000 arms, enabling him to see and help all suffering beings

Following the Bodhisattva Path means practising the Six Perfections (Paramitas).

- Dana – giving or generosity. An attitude of generosity, in thought, word and deed; ultimately extended to all beings without expecting anything in return

- Shila – morality or ethics. The practice of the Precepts, based on the principle of ahimsa, or non-harm, and a deep respect for all life

- Virya – energy. A natural, persistent effort to work for the benefit of all beings

- Kshanti – patience or forbearance. The confidence and composure to acknowledge people and things as they are

- Samadhi – meditation. The development of constant awareness, concentration and clarity of mind

- Prajna – Wisdom. Insight into the true nature of reality, and deep understanding of the interconnectedness of all things

3. Tibetan Buddhism

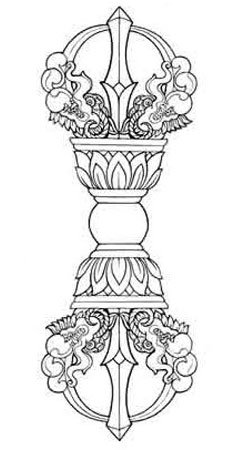

Vajrayana – the Diamond Way

Vajrayana – the Diamond Way

Samye, the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet, was built in the 7th century. It was modelled on the great Indian university monasteries, but its construction met with so much opposition that the king had to send for the great Indian saint-magician Padmasambhava. He introduced into Tibet a magical-ritual form of Buddhism from India, known as Tantric Buddhism or the Vajrayana (the Diamond Way). Practitioners of this form of Buddhism believe that full engagement in ritual Tantric practices incorporates all their energies, helping them achieve their quest for Enlightenment. Tibetan Buddhism draws on all three yanas, or forms of Buddhism: Hinayana, Mahayana and Vajrayana.

Monastic universities

In Tibet’s great monastic universities, monks and nuns spend many years studying Mahayana texts. As part of their training they undergo rigorous oral exams and debates. They also take the Bodhisattva Vow – a vow to pursue Enlightenment not just for themselves but for the sake of all beings. Many Tibetan Buddhists, monastic or lay, take the Bodhisattva Vow. The word bodhisattva means a being dedicated to Enlightenment.

Lineage

A key feature of Tibetan Buddhism is an emphasis on the transmission of the teaching from the master, or guru, to the disciple, as part of a carefully preserved lineage. The differences between the schools in Tibetan Buddhism are not primarily based on differences of rule or doctrine, but on lineage.

The four main Tibetan schools are

- The Nyingmapa School (‘the old ones’) who trace their origins back to Padmasambhava

- The Shakyapa School

- The Gelugpa school is headed by the Dalai Lama

- The Kagyupa school begins its lineage with Naropa, the Indian sage, followed by the Tibetan yogi and mystic poet Milarepa, and his follower, Gampopa. It was this school that introduced the practice of finding the reincarnations of deceased lineage holders to train from childhood. The Karmapa Order, based at Samye Ling Monastery and Tibetan Centre, is a particular lineage within the Kagyupa School. Kagyu Samye Ling in Scotland was the first Tibetan Buddhist centre established in the West.

One of the Tibetan schools most active in the West is the The New Kadampa Tradition (NKT), a Tibetan school devoted to promoting Mahayana Buddhism. Founded by Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, it is based at The Manjushri Centre, Cumbria. The NKT has about 80 Centres in the UK.

4. Zen Buddhism

The Golden Flower

The Golden Flower

Zen Buddhism is a Mahayana tradition which developed from Ch’an, which is the Chinese pronunciation of the Pali and Sanskrit word dhyana. Dhyana refers to states of deep concentration in meditation.

The Zen tradition tells how the Buddha, while seated before a large assembly of monks, silently held aloft a golden flower. The monk Mahakashyapa looked at the flower and smiled in understanding. The Buddha smiled too; he had communicated his teaching directly to Mahakashyapa, from mind to mind, beyond the use of words or concepts.

Ch’an

This, say the legends, was the start of the Ch’an, or Zen, lineage of teachers, a lineage which continued to be handed down personally from master to disciple. The records describe how the monk Bodhidharma took this form of Buddhism to China in the 5th century of the Common Era. Ch’an emphasises direct experience in sitting meditation, supported by the practice of mindfulness in daily life, as a means of breaking through to Enlightenment.

Zen

Ch’an combines the twin disciplines of meditation and challenging an over-reliance on conceptual thought. When Ch’an arrived in Japan the word ch’an became zen and two schools developed:

Rinzai Zen bases its practice on highly paradoxical dialogues with an Enlightened master as a means to gaining a sudden breakthrough to Enlightenment. The well known koans, such as ‘what is the sound of one hand clapping?’, or ‘what was your face before you were born?’, are records of these riddle-like exchanges between an Enlightened Ch’an or Zen master and disciples. (Koan means public record.)

Soto Zen pursues a gradual Awakening through the practice of the Precepts, zazen or ‘Just Sitting’ meditation, and the practice of mindfulness in daily life. Through these practices, one realizes one’s true unlimited potential – one’s Buddha Nature.

5. Pure Land Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism is a Mahayana tradition which started in Japan.

Pure Land Buddhism is a Mahayana tradition which started in Japan.

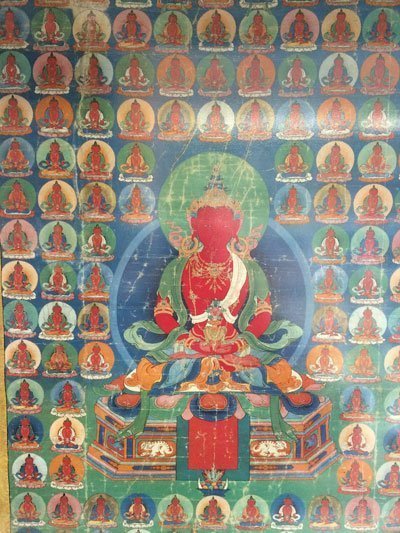

The Pure Land Sutras

The sacred texts of Pure Land Buddhism describe how the Buddha taught his disciples about the existence of a Buddha called Amida, or Amitabha. Amida, the Buddha of Infinite Light, lives beyond time in a Pure Land.

Shinran

In the famine-struck, war-torn Japan of the 12th century, this highly devotional form of Buddhism came to full flowering as a separate school, known as True Pure Land, or Jodo Shin Shu. Its founder, Shinran, taught that reliance on simple faith, and recitation of the name of Amida leads to rebirth in his Pure Land, where Enlightenment is not only assured but easy to pursue. For Pure Land Buddhists, the key is to let go of the illusion of self and give oneself up to the saving power of Amida’s vow.

Amida’s Vow

The whole of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism rests on the vow of Amida. The texts describe how, as a monk countless ages ago, Amida took the Bodhisattva Vow and promised not to enter Enlightenment and become a Buddha until he had established a Pure Land. Merely calling his name in great faith and devotion assures entry into this Pure Land at the moment of death. All that is needed is to abandon an egocentric reliance on self and to rely instead on the power of Amida.

True Pure Land Buddhism has been handed down through a hereditary married priesthood.

6. Triratna (formerly FWBO)

Venerable Urgyen Sangharakshita became a Buddhist in his teens. After the Second World War he spent twenty years in India, where he was ordained as a Theravadin monk in 1950 and studied with eminent Tibetan and Chinese Buddhist teachers. Returning to Britain in 1966, and recognising a growing interest in Buddhism, he sought to communicate the essence of the Buddha’s teachings in a manner relevant to life in the modern industrialised West.

Venerable Urgyen Sangharakshita became a Buddhist in his teens. After the Second World War he spent twenty years in India, where he was ordained as a Theravadin monk in 1950 and studied with eminent Tibetan and Chinese Buddhist teachers. Returning to Britain in 1966, and recognising a growing interest in Buddhism, he sought to communicate the essence of the Buddha’s teachings in a manner relevant to life in the modern industrialised West.

Triratna Buddhist Community (formerly The Friends of the Western Buddhist Order)

Sangharakshita founded the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (now known as Triratna Buddhist Community) in 1967, drawing on the whole of the Buddhist tradition rather than just one school. He also sought to draw on positive aspects of modern Western culture, such as art, poetry and literature, to support and inspire Buddhist practice.

The Triratna Buddhist Order

The Order itself was founded the following year, in 1968. Members of the TBO are neither monastic nor lay; in being ordained, these women and men commit themselves to following the teachings of the Buddha. Whatever their lifestyle – whether celibate, single or married, living alone, with a family, a partner or in a Buddhist residential community – their commitment to Go for Refuge to the Three Jewels – the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha – is primary.

Triratna Centres

There are about 30 Triratna centres in the UK, engaged in teaching meditation and Buddhism as well as providing a focus for other Sangha activities. They are run by members of the Triratna Buddhist Order.

Communities

Close by many Triratna centres there are also communities for men and women. These single-sex communities offer a supportive enviroment for spiritual practice and the chance to deepen friendships with others who share the same ideals and interests.

Team-Based Right Livelihood Businesses

These Buddhist businesses provide an opportunity for members of the Sangha to practise with fellow Buddhists whilst working and earning a living.

Scripture and Authority

The Pali Canon (Tipitaka)

The Pali Canon is also known as the Tipitaka (ti = three; pitaka = basket), meaning the Three Baskets, or Collections, of teachings. These are:

The Pali Canon is also known as the Tipitaka (ti = three; pitaka = basket), meaning the Three Baskets, or Collections, of teachings. These are:

The Vinaya Pitaka, the document recording the code of discipline by which early monks and nuns were to live. A fixed set of rules was agreed at the First Sangha Council (see below) but not set down as a written code until the 1st century BCE. Monastics of the Theravada tradition still live by the Pali vinaya; other monastic traditions live by slightly varying vinayas.

The Sutta Pitaka, the discourses or sermons of the Buddha, given to disciples in all walks of life, both lay and monastic. The term sutta (sutra in Sanskrit) means ‘thread’ and is related to the English term ‘suture’; thus, a sutta is a threaded, or connected, series of teachings on a given theme.

The Abhidhamma Pitaka, an intricate analysis and classification of mental states, phenomena, character-types, major Dharma-topics, and paticcasamuppada, as well as a definition of Dharma-terms. This pitaka is later than the first two, most of it having been compiled between the 3rd century BCE and the 1st century CE.

The Pali Canon as a source of authority

The Pali Canon is the central source of authority for Buddhist belief and practice; the textual source for the earliest, commonest and most central Buddhist teachings. Such formulations as the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path and the Threefold Way are repeatedly to be found woven into the narrative of various suttas.

The suttas also include descriptions of the religious experience of the Buddha and his followers or other listeners: there are those who describe extremely refined and elevated states of mind achieved in meditation; and those who gain Enlightenment on hearing the Buddha, having sought him out, inspired by the possibility of the very existence of an Enlightened being.

Of the three Pitakas of the Pali Canon, the Sutta Pitaka has the most universal significance to Buddhists, in that it is addressed to listeners both lay and monastic. However, running to many times the length of the Bible, it is most commonly found in monasteries and libraries; and very rarely in a lay household. Individual lay Buddhists are much more likely to have edited collections, or small sections such as the Dhammapada. Many may have no scriptures at all.

Though regular Dharma study is considered of great benefit, it is not necessary to have studied great quantities of Buddhist scripture to be able to practise the Buddha’s teachings: many of the world’s Buddhists may be unable to read; hundreds of scriptures have yet to be translated into any Western languages; and meditation and ethical practice are also central means of self-transformation. In many Asian Buddhist countries, lay people may not have heard much scripture, their role being largely that of supporting the monks and nuns. With the arrival of Buddhism in the West, however, the divide between monastic and lay practice seems to be becoming less distinct, with many very committed and educated lay people studying the scriptures in translation.

Dhammapada

The Dhammapada is probably the best-known section of the Pali Canon. A small collection of 423 verses concerned with the ‘way’ or ‘footsteps’ (pada), of the truth (Dhamma), its first two verses sum up the teaching of karma.

The Dhammapada is probably the best-known section of the Pali Canon. A small collection of 423 verses concerned with the ‘way’ or ‘footsteps’ (pada), of the truth (Dhamma), its first two verses sum up the teaching of karma.

1. What we are today comes from our thoughts of yesterday, and our present thoughts build our life of tomorrow: our life is the creation of our mind.

If a man speaks or acts with an impure mind, suffering follows him as the wheel of the cart follows the beast that draws the cart.2. What we are today comes from our thoughts of yesterday, and our present thoughts build our life of tomorrow: our life is the creation of our mind.

If a man speaks or acts with a pure mind, joy follows him as his own shadow.

A section from the Pali Canon: the Buddhavagga

The text is translated by Urgyen Sangharakshita.

Buddhavagga (The Section of the Enlightened One)

Background: A vagga is a section. The Dhammapada comprises 26 sections of which the Buddhavagga is a collection of verses about the nature and actions of an Enlightened Being and his/her effect on others. This teaching is addressed to all, lay or monastic.

1 That Enlightened one whose sphere is endless, whose victory is irreversible, and after whose victory no (defilements) remain (to be conquered), by what track will you lead him (astray), the Trackless One?

2 That Enlightened One in whom there is not that ensnaring, entangling craving to lead anywhere (in conditioned existence), and whose sphere is endless, by what track will you lead him (astray), the Trackless One?

3 Those wise ones who are intent on absorption (in higher meditative states) and who delight in the calm of renunciation, even the gods love them, those thoroughly Enlightened and mindful ones.

4 Difficult is the attainment of the human state. Difficult is the life of mortals. Difficult is the hearing of the Real Truth (saddhama). Difficult is the appearance of the Enlightened Ones.

5 The not doing of anything evil, undertaking to do what is (ethically) skilful (kusala), (and) complete purification of the mind – this is the ordinance (sasana) of the Enlightened Ones.

6 Patient endurance is the best form of penance. ‘Nirvana is the Highest,’ say the Enlightened Ones. No (true) goer forth (from the household life) is he who injures another, nor is he a true ascetic who persecutes others.

7 Not to speak evil, not to injure, to exercise restraint through the observance of the (almsman’s) code of conduct, to be moderate in diet, and to occupy oneself with higher mental states – this is the ordinance (sasana) of the Buddhas.

8 Not (even) in a shower of money is satisfaction of desires to be found. ‘Worldly pleasures are of little relish, (indeed) painful.’ Thus understanding, the spiritually mature person

9 takes no delight even in heavenly pleasures. The disciple of the Fully, Perfectly Enlightened One takes delight (only) in the destruction of craving.

10 Many people, out of fear, flee for refuge to (sacred) hills, woods, groves, trees and shrines.

11 In reality this is not a safe refuge. In reality this is not the best refuge. Fleeing to such a refuge one is not released from all suffering.

12 He who goes for refuge to the Enlightened One, to the Truth, and to the Spiritual Community, – and who sees with perfect wisdom the Four Ariyan Truths, –

13 namely, suffering, the origin of suffering, the passing beyond suffering, and the Ariyan Eightfold Way leading to the pacification of suffering, –

14 (for him) this is a safe refuge, (for him) this is the best refuge. Having gone to such a refuge, one is released from all suffering.

15 Hard to come by is the Ideal Man (purisajanna). He is not born everywhere. Where such a wise one is born, that family grows happy.

16 Happy is the appearance of the Enlightened Ones. Happy is the teaching of the Real Truth (saddhama). Happy is the unity of the Spiritual Community. Happy is the spiritual effort of the united.

17 He who reverences those worthy of reverence, whether Enlightened Ones or (their) disciples, (men) who have transcended illusion (papanca), and passed beyond grief and lamentation,

18 he who reverences those who are of such a nature, who (moreover) are at peace and without cause for fear, his merit is not to be reckoned as such and such.

Metta Sutta (sermon on Loving-Kindness)

This is what should be done

This is what should be done

By those skilled in goodness

Who know the place of peace:

Let them be able and upright,

Sraightforward and gentle in speech;

Humble and not conceited;

Contented and easily satisfied;

Unburdened with duties and frugal in their ways;

Peaceful and calm, and wise and skilful,

Not proud or demanding in nature.

Let them not do the slightest thing

that the wise would later reprove.

Wishing, in gladness and in safety,

may all beings be at ease.

Whatever living beings there may be;

And whether they be weak or strong, omitting none,

The great or the mighty, medium, short or small,

The seen and the unseen,

Those living near and far away,

Those born and to-be-born –

May all beings be at ease!

Let none deceive another,

Or despise any being in any state.

Let none through anger or ill-will

Wish harm upon another.

Even as a mother protects with her life

Her child, her only child,

So with a boundless heart should one cherish all living beings;

Radiating kindness over the entire world;

Spreading upward to the skies

And downward to the depth,

Outward and unbounded,

Freed from hatred and ill-will.

Whether standing or walking, seated or lying down

Free from drowsiness,

One should sustain this recollection.

This is said to be the sublime abiding.

By not holding to fixed views,

The pure-hearted, having clarity of vision

Being freed from all sense desires, is not born again to this world.

Kalama Sutta

from the Anguttara Nikaya.

from the Anguttara Nikaya.

The text is translated by Urgyen Sangharakshita.

Background

In the town of Kesaputta, in Kosala, northern India, a group from the Kalama tribe seek the Buddha’s advice. Confused by teachers proclaiming contradictory ideas, they wonder how to decide whose teaching to follow. Respecting the fact that they are not his followers and that their views may differ from his, the Buddha advocates testing teachings against experience.

The Kalamas are so impressed with his teaching that they become his lay followers; they go for refuge to the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha as the only true sources of security in this life.

Text

Thus have I heard: On a certain occasion the Exalted One, while going his rounds among the Kosalans with a great company of monks, cam to Kesaputta, a district of the Kosalans.

Now the Kalamas of Kesaputta heard it said that Gotama the recluse, the Sakyans’ son who went forth as a wanderer from the Sakyan clan, had reached Kesaputta.

And this good report was noised abroad about Gotama, that Exalted One, thus: “He it is, the Exalted One, Arahant, a Fully Enlightened One, perfect in knowledge and practice, and so forth. It were indeed a good thing to get sight of such arahants!”

So the Kalamas of Kesaputta came to see the Exalted One. On reaching him, some saluted the Exalted One and sat down at one side; some greeted the Exalted One courteously, and after the exchange of greetings and courtesies sat down at one side; some raising their joined palms to the Exalted One sat down at one side; some proclaimed their name and clan and did likewise; while others without saying anything just sat down at one side. Then as they sat thus the Kalamas of Kesaputta said this to the Exalted One:

“Sir, certain recluses and brahmins come to Kesaputta. As to their own view, they proclaim and expound it in full; but as to the view of others, they abuse it, revile it, depreciate and cripple it. Moreover, sir, other recluses and brahmins, on coming to Kesaputta, do likewise. When we listen to them, sir, we have doubt and wavering as to which of these worthies is speaking truth and which speaks falsehood.”

“Yes, Kalamas, you may well doubt, you may well waver. In a doubtful matter wavering does arise. Now look you, Kalamas, be not misled by report or tradition or hearsay; be not misled by proficiency in the collections, nor by mere logic or inference, nor after considering reasons, nor after reflection on and approval of some theory, nor because it fits becoming, nor out of respect for a recluse who holds it. But, Kalamas, when you know for yourselves, these things are unprofitable, these things are blameworthy, these things are censure by the intelligent; these things, when performed and undertaken, conduce to loss and sorrow, then indeed do ye reject them, Kalamas.

Now what think ye, Kalamas? When greed arises within a man, does it arise to his profit or to his loss?

“To his loss, sir.”

Now Kalamas, does not this man, thus become greedy, being overcome by greed and losing control of his mind, does he not kill a living creature, take what is not given, go after another’s wife, tell lies and lead another into such a state as cause his loss and sorrow for a long time?”

“He does, sir.”

“Now what think ye, Kalamas? When malice arises within a man, does it arise to his profit or two his loss?”

“To his loss, sir.”

“Now, Kalamas, does not this man, thus become malicious, being overcome by malice and losing control of his mind, does he not kill a living creature, take what is not given, go after another’s wife, tell lies and lea another into such a state as cause his loss and sorrow for a long time?”

“He does indeed, sir.”

“Now what think ye, Kalamas? When illusion arise within a man, does it arise to his profit or to his loss?”

“To his loss, sir.”

“Now, Kalamas, does not this man, thus deluded likewise lead another to his loss and sorrow for a long time?”

“He does, sir.”

“Well then, Kalamas, what think ye? Are these things profitable or unprofitable?”

“Unprofitable, sir.”

“Are they blameworthy or not?”

“Blameworthy, sir.”

“Are they censured by the intelligent or not?”

“They are censured, sir.”

“If performed and undertaken, do the conduce to loss and sorrow or not?”

“They conduce to loss and sorrow, sir. It is just so, methinks.”

“So, then, Kalamas, as to my words to you just now: ‘Be not misled by proficiency in the collections, nor by mere logic or inference, nor after considering reasons, nor after reflection on and approval of some theory, nor because it fits becoming, nor out of respect for a recluse who holds it. But, Kalamas, when you know for yourselves: these things are unprofitable, these things are blameworthy, these things are censured by the intelligent; these things, when performed and undertaken, conduce to loss and sorrow, then indeed do ye reject them, such was my reason for uttering those words.

Come now, Kalamas, be ye not so misled. But if at any time ye know of yourselves: these things are profitable, they are blameless, they are praised by the intelligent; these things when performed and undertaken, conduce to profit and happiness, then, Kalamas, do ye, having undertaken them, abide therein.

Now what think ye, Kalamas? When freedom from greed arises within a man, does it arise to his profit or his loss?”

“To his profit, sir.”

“Does not this man, not being greedy, not overcome by greed, having his mind under control, does he not cease to slay and so forth; does he not cease to mislead another into a state that shall be to his loss and sorrow for a long time?”

“He does, sir.”

“Now what think ye, Kalamas? When freedom from malice arises within a man, does it arise to his profit or his loss?”

“To his profit, sir.”

“Does not this man, not being malicious, not being overcome by malice, but having his mind under control, does he not cease to slay and so forth? Does he not lead another into such a state as causes his profit and happiness for a long time?”

“He does, sir.”

“And is this not the same with regard to freedom from illusion?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then, Kalamas, what think ye? Are these things profitable or unprofitable?”

“Profitable, sir.”

“Are they blameworthy or not?”

“They are not, sir.”

“Are they censure or praised by the intelligent?”

“They are praised, sir.”

“When performed and undertaken, do they conduce to happiness or not?”

“They do conduce to happiness, sir. It is just so, methinks.”

“So, then Kalamas, as to my words to you just now: ‘Be ye not misled, but when ye know for yourselves: these things are profitable and conduce to happiness, do ye undertake them and abide therein.’ such was my reason for uttering them.

Now Kalamas, he who is an Ariyan disciple freed from coveting and malevolence, who is not bewildered but self-controlled and mindful, with a heart possessed by goodwill, by compassion, possessed by sympathy, by equanimity that is widespread, grown great and boundless, free from enmity and oppression, such a one abides suffusing one quarter of the world therewith, likewise the second, third and fourth quarter of the world. And in like manner above, below, across, everywhere, for all sorts and conditions, he abides suffusing the whole world with a heart possessed by equanimity that is widespread, grown great and boundless, free from enmity and oppression. By that Ariyan disciple whose heart is thus free from enmity, free from oppression, untainted and made pure, by such in this very life four comforts are attained, thus:

‘If there be a world beyond, if there be fruit and ripening of deeds done well or ill, then when body breaks up after death, I shall be reborn in the Happy Lot, in the Heaven World.’ This is the first comfort he attains.

‘If, however, there be no world beyond, no fruit and ripening of deeds done well or ill, yet in this very life do I hold myself free from enmity and oppression, sorrowless and well.’ This is the second comfort he attains.

‘Though as a result of action, ill be done by me, yet do I plan no ill to anyone. And if I do no ill, how can sorrow touch me?’ This is the third comfort he attains.

‘But if, as a result of action, no ill be done by me, then in both ways do I behold myself utterly pure.’ This is the fourth comfort he attains.

Thus, Kalamas, that Ariyan disciple whose heart is free from enmity, free from oppression, untainted and made pure, in this very life attains these four comforts.”

“So it is, Exalted One, So it is, Welfarer. That Ariyan disciple in this very life attains these four comforts…” And they repeated all that had been said.

“Excellent, sir! We here do go for refuge to the Exalted One, to Dhamma and to the Order of monks. May the Exalted One accept us as lay-followers from this day forth so long as life shall last, who have so taken refuge.”

Worship and Celebration

Worship in Buddhism

Buddhism doesn’t have God at its centre but people still worship. Buddhists recite devotional verses called puja (pronouced poo-ja). These are directed to the Three Jewels: the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Puja simply means worship, and worship is what we can do when we recognise something is of value, of worth (worth-ship). Obviously a Buddhist sees great value in the Three Jewels and what they represent.

Buddhism doesn’t have God at its centre but people still worship. Buddhists recite devotional verses called puja (pronouced poo-ja). These are directed to the Three Jewels: the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Puja simply means worship, and worship is what we can do when we recognise something is of value, of worth (worth-ship). Obviously a Buddhist sees great value in the Three Jewels and what they represent.

Buddhists around the world recite the Refuges and Precepts. They might recite these in the morning before they begin work, and at other times as a way of reminding themselves of their buddhist values.

In a Triratna centre people may get together and recite a Sevenfold Puja, as a way to more poetically remind themselves of the value of the three jewels. They recite verses to the three jewels, chant mantras and make offerings. They may hear a reading about the life of the Buddha, or a teaching to inspire them. People often feel peaceful at the end of a puja having voiced appreciation of what is important to them. But in Buddhism people have a choice. Not everybody responds to chanting verses, and may use other methods to bring what’s important to mind.

The chanting of mantras

A mantra is a series of sounds that put together make a kind of sound picture. An example is the famous mantra OM MANI PADME HUM pictured on the right. Perhaps you can see the 6 syllabuses in the Tibetan script for Om Ma Ni Pad Me Hum?

A mantra is a series of sounds that put together make a kind of sound picture. An example is the famous mantra OM MANI PADME HUM pictured on the right. Perhaps you can see the 6 syllabuses in the Tibetan script for Om Ma Ni Pad Me Hum?

Each mantra is a kind of sound symbol for an enlightened Buddhist figure. This one represents Avalokitesvara (pronounced Avalo-kit-esh-vara), the bodhisattva of compassion, who wants to help people who are suffering. When we chant his mantra, we are reminded of how important it is to help people. Man-tra means mind-protector. Chanting his mantra protects us from being too wrapped up with ourselves which isn’t too good for us in the long run.

Lots more information on the meaning of this mantra.

Why do Buddhists bow?

Like so many aspects of Buddhist practice, there are as many answers to this as there Buddhists – it is an individual affair. However, most Buddhists put their hands together and bow when they see a buddhist shrine as a sign of respect. It is like saying they feel OK with the Buddha and are open to learning from him. A disciple bows to a master for this reason. In the same way, karate students bow to their sensei (teacher) when they enter the dojo (training space). By lowering their heads they are doing a ritual action that symbolises accepting the guidance and discipline of a teacher. When we do a ritual action like this it can be more powerful than just thinking, because it is a bodily action and that gives it more weight, has more influence on our minds.

Like so many aspects of Buddhist practice, there are as many answers to this as there Buddhists – it is an individual affair. However, most Buddhists put their hands together and bow when they see a buddhist shrine as a sign of respect. It is like saying they feel OK with the Buddha and are open to learning from him. A disciple bows to a master for this reason. In the same way, karate students bow to their sensei (teacher) when they enter the dojo (training space). By lowering their heads they are doing a ritual action that symbolises accepting the guidance and discipline of a teacher. When we do a ritual action like this it can be more powerful than just thinking, because it is a bodily action and that gives it more weight, has more influence on our minds.

A bow could be little more than a slight nod of the head, or could be a full-length prostration, where the front of one’s body is against the floor, with one’s nose pressed against the ground! You can imagine the effect that could have on one’s ego or pride! It is actually a sign of maturity to acknowledge that someone is greater than oneself – not putting oneself down but recognising that objectively they are better in certain respects. If one doesn’t have a sense of reverence, receptive to something higher, then we won’t aspire to become greater than we already are.

What do you think about this?

Living the Buddhist Life

Ahimsa and the Precepts

Ahimsa: non-harm

The Pali word himsa means force.Ahimsa means no-force, or non-violence.

The Five Precepts form the basis of Buddhist ethics.

The first Precept expresses the principle of non-harm, or ahimsa.

The principle of ahimsa

- is based on an understanding of the interconnectedness of all life

- extends to all living beings

- covers any deliberate action of thought, word or deed

- involves avoiding deliberate harm and striving to bring about the greatest good

The other Precepts apply this principle to specific areas of behaviour, such as speech and sexual activity.

The Five Precepts

I undertake to abstain from taking life.With deeds of loving kindness I purify my body.

I undertake to abstain from taking what has not been given.With open handed generosity I purify my body.

I undertake to abstain from sexual misconduct.With stillness, simplicity and contentment I purify my body.

I undertake to abstain from false speech.With truthful communication I purify my speech.

I undertake to abstain from intoxicants that cloud the mind.With mindfulness, clear and radiant, I purify my mind.

Guidelines for Living

For Buddhists, the Five Precepts provide guidelines for leading an ethical life.The Precepts

- apply to all relationships including marriage, family life and sexual relationships

- express the principle of ahimsa or non-harm

- are based on an understanding of the interconnectedness of all life

- extend to all beings

- cover any deliberate action of thought, word or deed

- indicate harmful behaviour to avoid and positive behaviour to develop

- are not commandments, but a set of principles taken on voluntarily – in Buddhism there is no God to lay down commandments

Lists of Precepts occur in several places in the Buddhist scriptures. The following is taken from the Anguttara-Nikaya (The Book of Gradual Sayings) in the Sutta Pitaka of the Pali canon.

When a lay follower possesses five things,

he lives with confidence in his house,

and he will find himself in heaven

as sure as if he had been carried off and put there.

What are the five?

He abstains from:

killing breathing things,

from taking what is not given,

from misconduct in sensual desires,

from speaking falsehood,

and from indulging in liquor, wine, and fermented brews.

The basic Precepts are the same for all Buddhists, but at their ordination monks and nuns take on a vinaya, or set of rules of conduct. These rules of conduct differ from one tradition or school to another.

Metta and Karuna

Metta (Sk, maitri), karuna, mudita and upekkha (Sk. upeksha) are the Four Brahma Viharas, or Divine Abodes. Mudita is the quality of rejoicing in the happiness of others. Upekkha is the quality of equanimity, a calm, even joy unruffled by life’s events

Metta (Sk, maitri), karuna, mudita and upekkha (Sk. upeksha) are the Four Brahma Viharas, or Divine Abodes. Mudita is the quality of rejoicing in the happiness of others. Upekkha is the quality of equanimity, a calm, even joy unruffled by life’s events

Metta: Universal Loving Kindness

Metta is

- based on a deep understanding of the interconnectedness of all living things

- an attitude of the heart and mind that unconditionally seeks the well being of all

- the antidote to hatred or ill will

If you know your own good

and know where peace dwells

then this is the task:Lead a simple and a frugal life

uncorrupted, capable and just;

be mild, speak soft, eradicate conceit,

keep appetites and senses calm.Be discreet and unassuming;

do not seek rewards.

Do not have to be ashamed

in the presence of the wise.May everything that lives be well!

Weak or strong, large or small,seen or unseen, here or elsewhere,

present or to come, in heights or depths,

may all be well.Have that mind for all the world –

get rid of lies and pride –

a mother’s mind for her baby,

her love, but now unbounded.Secure this mind of love,

no enemies, no obstructions,

wherever or however you may be!It is sublime, this,

it escapes birth and death,

losing lust and delusion,

and living in the truth!

The Metta Bhavana meditation is a practice which helps develop an attitude of well-wishing towards all living beings. There are five stages to the meditation:

- First one develops an attitude of kindness, appreciation and well-wishing towards oneself, then one extends this to include:

- a good friend

- a person one doesn’t feel much connection with

- a person one dislikes

- all living beings

Bhavana means cultivation of, or bringing into being.

Work and money

Gelongma Lhamo is a nun at Samye Ling monastery and Tibetan Centre, Scotland.

Gelongma Lhamo is a nun at Samye Ling monastery and Tibetan Centre, Scotland.

Money

As a fully ordained nun I have a vow not to handle money or objects of great value. But these vows were designed in the time of the Buddha, two and a half thousand years ago. Never to handle money would be wonderful, but a bit impractical, so I have a very small allowance, for trips to see family, or essentials such as toothpaste and soap.

Work

I’ve been a nun for just over ten years. Before that I lived in a city and worked as a computer programmer. When I was first a Buddhist, I thought I needed to give up my work and spend all my time practising but it gradually dawned on me that there was a wealth of opportunity for training my mind in everyday life: getting on well with the people I worked with rather than giving in to anger, ambition or greed.

These opportunities also present themselves at Samye Ling. One of the main reasons we place so much emphasis on work is that we can learn so much through it. Though most of us think that it is an excellent thing to do to spend all our time meditating, most of us find that we are not really capable of it. We can daydream. Whereas if we are working with somebody who’s telling us that really we’re doing things wrongly we’ve got no choice but to look at the situation and try and come up with some kind of solution. It’s a very useful method of spiritual development.

So in order to provide as many people as possible with a way of accessing the Dharma and benefiting from it, we spend large amounts of every day working. There are people who do building work, people who do office work, people who clean or cook: everything that needs to be done. And I work in the office mostly.

Brian Gay is a lay minister associated with the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives (Soto Zen) at Throssel Hole Abbey, Northumberland.

Brian Gay is a lay minister associated with the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives (Soto Zen) at Throssel Hole Abbey, Northumberland.

Money

I don’t think money is a problem. I think it’s what you do with it that’s the interesting thing!

Work

What’s great about the Zen system is that we have a range of great stories of old Zen Masters. There’s the classic one about an 80 year-old Zen Master who refused food because he’d been ill and he hadn’t worked in the gardens and when they hammered on his door and said “Come on! You’ve got to have your food”, he said, “A day without work is a day without food.”

I’ve been coming to Throssel Hole since 1988 and I became a lay minister within the Order in 1993. The work I do is as a management consultant: some of my work is in London; some is local with voluntary organisations and it’s around the area of management development, organisational development and one-to-one personal development.

Although the monks have in a sense renounced the world they do an awful lot of hard work. They actually built this place. OK, the lay people helped them, but they built it, they work in the gardens, they do the stonemasonry. They repair the tractor; they planted the trees. All this is work. So I see nothing strange in having a different form of practice as a lay person, which is centred upon work.

Right Livelihood is actually part of the practice and part of my work. That’s because the practice is about helping individuals to realise who they really are and what their true nature is; and the work I’m involved with, at the individual level, is about helping individuals realise their true potential, to see situations differently, to find solutions to the problems that face them.

Family values and sexual ethics

The Third Precept

The Third Precept – abstaining from misconduct in sensual desires – applies the principle of ahimsa, non-harm, to sexual behaviour.

- sensual misconduct is sexual behaviour that causes harm, to oneself or others

- its cause is craving or greed, hatred and ignorance

- traditionally rape and abduction were cited as examples of sexual misconduct

- the opposite of sexual craving is the cultivation of stillness, simplicity and contentment

The goal of Buddhism is the attainment of Nirvana (Nibbana in Pali), or Enlightenment. The word nirvana literally means a blowing out – of the fires of craving or greed, hatred and ignorance.

Celibacy

The Buddha lived a celibate life and encouraged those of his followers who were able to do likewise. The third Precept for monks and nuns is to observe celibacy; i.e. not to engage in any sexual activity of body, speech or mind. Celibacy enabled monks and nuns to remain free from family responsibilities and to work to overcome the craving associated with sexual activity.

Marriage and Divorce

Within Buddhism

- marriage is a secular arrangement, not a sacrament or holy rite

- monks do not conduct the marriage ceremony, but often bless the couple

- it is recognised that divorce may be necessary if the two people concerned cannot live together happily

- a variety of marriage laws and customs and patterns of family life exist in different traditions

STORIES from the BUDDHIST TRADITION - ages 12 and up

These stories, for aged 12 and up, are accessible versions or a ‘re-telling’ of traditional texts from the Pali Canon. They don’t assume any prior knowledge, can be used in any order, and you are welcome to adapt them for your own purposes.

They are offered freely as pdfs, with thanks to Richard Winter from the Cambridge Buddhist Centre.

- Ajatasattu: the value of a life of simplicity, contentment and meditation

- Angulimala: the possibility of transforming one’s life and the difficulties involved in this

- Bahiya: the search for wisdom – beyond words and concepts

- Early Life of the Buddha: the nature of the Buddha’s wisdom

- Elephant and Opinions: why people are convinced that their own wrong opinions are the truth

- Kalamas’ questions: how to distinguish true teachings from the variety of ‘opinions’

- Karma: our good and bad actions always have good and bad consequences

- Kisa Gotami: bereavement, grief and compassion for humanity as a whole

- Meghiya: the importance of friendship in making spiritual progress

- Ocean and Wisdom: the nature of wisdom and the path to wisdom

- Signs ‘Mangala’: the many different aspects of the spiritual life

- Tathagatagarbha (hidden wisdom): each of us already has a hidden Buddha Nature

- Women’s stories 1: are there spiritual differences between women and men? Also the nature of ‘mental control’

- Women’s stories 2: spirituality and beauty, spirituality and physical pleasures